Read Transcript EXPAND

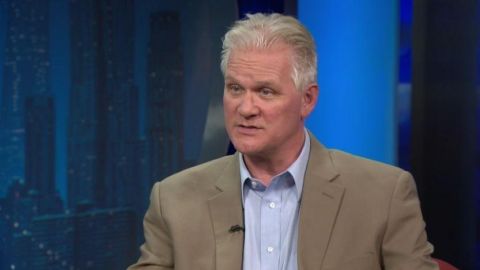

HARI SREENIVASAN: A free taxi. Explain this idea, how you came up with it.

FRANK LANGFITT, AUTHOR, “THE SHANGHAI FREE TAXI”: Sure. So in 2011 — I had worked in China going back to, I guess about 1997. And so I had a feel for the country but I had been away for about 10 years as a reporter and I returned in 2011. And I could see that the country changed dramatically. Certainly, economically. But you could also see that there were big problems with the corruption and the Communist Party was losing the hearts and minds of the people very rapidly. And I wanted to try to figure out where the country was going but do it in a different sort of way. So a foreign reporter, particularly American reporter, asking political questions of ordinary Chinese is kind of a non- starter. I had been a taxi cab driver years and years ago. And I found that was a great way to get to know Philadelphia, my hometown. So I decided I would set up a free taxi with no idea whether anyone would actually get in it. And I drove out and tried and so it happened.

SREENIVASAN: So this isn’t like one of those Cash Cab?

LANGFITT: No, no.

SREENIVASAN: The cameras are not rolling when you get in?

LANGFITT: No.

SREENIVASAN: It’s a normal taxi?

LANGFITT: Well, what it is, is I didn’t know actually how to do this. So I first went to a taxi company and said I would like to be a taxi driver and they just laughed. And they said foreigners are not taxi drivers here. This isn’t going to work. So my wife came up with the idea, Julie, to get magnetic signs and put them on a rental car and my news assistant that I was working within Shanghai, he came up with a great slogan which was (INAUDIBLE) in Chinese which means make Shanghai friends, chat about Shanghai life.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(FOREIGN LANGUAGE)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

LANGFITT: And it was called (FOREIGN LANGUAGE) which loosely translated is free loving heart taxi. It sounds much better in Mandarin than it does in English.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

LANGFITT: But the message got through, I think.

SREENIVASAN: Clearly, you speak Chinese.

LANGFITT: I do.

SREENIVASAN: That’s not a hurdle. Driving in China?

LANGFITT: Challenging. I’m glad I don’t do it anymore. It’s a game of inches. It’s sort of a metaphor for competition in, you know, a country of 1.4 billion people. So Shanghai, 26 million people. More and more cars every day. And to get to drive the city, you have to be very very careful because back when I was driving, there weren’t many rules. And so you just kind of inch through traffic and you have to always be concentrating. At the same time, chatting with a passenger and trying to figure out could this be an interesting character in a radio story.

SREENIVASAN: Yes. So now people are getting into this taxi. Here is a tall white guy who is offering them a free ride to wherever.

LANGFITT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: So how does this turn into relationships that lead to wonderful stories?

LANGFITT: Actually, being a foreigner, in this case, was an advantage.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

LANGFITT: There’s a lot of distrust in Chinese society. A lot of Chinese, there’s a lot of scams that go on in places like Shanghai and Beijing and a lot of Chinese don’t trust each other. A foreigner would actually be seen as more honest.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

LANGFITT: And so I think have I been doing it as a Chinese person, I might not have gotten many takers. And I remember actually one time where I met these two factory workers, girls from the countryside who were coming into Shanghai and had wanted me to take them to a tourist destination. But they — literally, there was this approach of avoidance. Like they were afraid to get in the cab. And there was a ferry worker, I was hanging out a ferry stop in Shanghai, and he said, “Oh, don’t worry, he’s fine. He’s a foreign friend. You can trust him.” And he said, “I wouldn’t have said that necessarily if you were Chinese.”

SREENIVASAN: Some of these trips that you take are pretty long.

LANGFITT: They are very long.

SREENIVASAN: I mean you took one out to the countryside. It’s like an amazing road trip.

LANGFITT: It was a wonderful road trip.

SREENIVASAN: And you’re the first person to take the wedding photo — I shouldn’t say the wedding photo but really of a new couple, married couple.

LANGFITT: It was. I mean I think that what we did with this case is after about a year of driving people around Shanghai, realized we really wanted to get out of the city, see more of the countryside, and kind of get a feel for how the country had transformed from a rural country to an urban one. And so I put an advertisement out on Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter and got — I offered to take people back home for Chinese New Year, which is the largest annual mass migration in the world, of course. And so it was a 500-mile drive. And when we started off, Hari, it was not easy to talk to people. I had my news assistant with a shotgun microphone and they didn’t really warm up. But you know how a drive is. It’s like in any culture. And once you get 100, 150 miles on, everybody just sort of forgot the microphone and just starts talking. And then you’re almost like old friends. And it was really fun to actually go to the wedding office to get the license with them and take the first photograph. And so I ended up becoming the wedding chauffeur in two weddings. And I also became the wedding photographer because I had a really good camera. And so at the end, I gave the families, you know, all the photos that I had.

SREENIVASAN: And these people are becoming friends over time. You’re following them not just on that taxi ride.

LANGFITT: No. And I don’t think anybody — I wouldn’t have wanted to write a book that was a thousand taxi rides in Shanghai. What I did is I was kind of, I guess you could say a little bit auditioning people, trying to find who were interesting folks who also were wide variety of people because I think China is increasingly more diverse in terms of points of view. So I met up a pajama salesman, a barber. I had a psychologist who I drove to see clients and then these two lawyers who had grown up — they’re brothers who grew up in the countryside who then moved to Shanghai, became lawyers, which is extraordinary. We’ve got two or three generations in most countries. And when I was last seeing them, they were working in the tallest building in all of China.

SREENIVASAN: Wow.

LANGFITT: And what was nice is I followed them for four or five years, their lives.

SREENIVASAN: Which in many ways is like, in every other country, would be 15 or 20 years.

LANGFITT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: Because they’re going through so many jobs, careers.

LANGFITT: So many changes. I mean people are changing jobs. So when I — the two men that I drove back and I drove in their weddings, they now have three kids.

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

LANGFITT: And so, you know, it was great to get to know them and also see how they were kind of grappling. Because the politics of the country changed, also, in ways that none of us anticipated when I started the project in 2014.

SREENIVASAN: So what did you notice changing even between the time that you had reported in China before and also the changes that were happening in front of you between 2014 and when you finished the project?

LANGFITT: Well, if you go back to 1997, most Chinese didn’t even have their own private homes. Most people that I knew worked in — had government apartments. And people didn’t have much wealth and Beijing was still probably more bicycles than cars. And the last time I was in Beijing, I hardly saw a bicycle. And what was really interesting is I had done this trip back to the countryside in 1998. Back then, I was working with uneducated migrant workers, blue collar, who couldn’t read very well and didn’t have many prospects. When I drove these folks back in 2015, they were white-collar people. And it was — what it came across is how in just 15 or 16 years, you’d seen a whole new professional class grow up in China with lots of opportunities. Passports, they traveled overseas, they owned their own apartments. It’s an extraordinary economic transformation. And overall, when you think of human development, a very positive story.

SREENIVASAN: You’re essentially witnessing one of the largest movements socially in sheer numbers of a group of people.

LANGFITT: Ever. I mean it’s astonishing. And I would say this about the characters. I think this is really important for people to remember when we think about the internal politics of China and the Communist Party is that rising tide did lift most — almost all boats. Every character that I talked to, regardless of where they were on the socioeconomic ladder, they’re much better off than their parents were. So some of them even — people say this, living the American dream in China.

SREENIVASAN: And that translates politically how? Because it used to be that question in America, are you better off now than you were four years ago and a year ago?

LANGFITT: Yes. Where I think it translates politically is that there’s a lot of residual support for this authoritarian regime. Because if you think about it, Hari, if you’re 30 years old, the lowest growth you’ve ever known, average GDP growth in a year is six percent.

SREENIVASAN: It’s stunning.

LANGFITT: It’s completely stunning. There’s never been a generation like this and I assume in human history. And so you can understand. I mean think about parties in this country, where I am in London, where I work now. If you had a political party that had delivered that kind of growth or at least overseen that kind of growth, it would be awfully hard to beat at the ballot box, even despite all the other problems.

SREENIVASAN: Is there a distinction there between country and party?

LANGFITT: That’s a great question. There is but the Communist Party would prefer that there not be and they’re very good at this. They try to — there’s even an anthem from the Civil War period in which they — or I guess the Revolutionary War where it’s without the Communist Party, there would be no new China. And what the party tries to do is make Chinese people, including some of my characters, think that to criticize the party is to criticize the country and not to differentiate. And I even have some characters that I talk to at great length who say, you know, there was a moment when I realized that they are different and that the party was trying to get me to think that they were both the same and that therefore I couldn’t be critical.

SREENIVASAN: And one of the other consequences of having such a dominant [13:45:00] single party, as you point out, so many of your characters in their lives today are benefitting from graft or conscious of graft. They just consider corruption part of the way of living through China.

LANGFITT: It has been that way for a long time and I think people were really sick of it. This was one of the things that really struck me when I did return in 2014 is government officials were stealing with both hands. We’re talking about trillions and trillions of dollars. I mean it’s sort of a pathological level of graft. And what Xi Jinping did when he got in which was extremely shrewd and absolutely necessary because I do feel the party was losing control. He did the biggest corruption crackdown in the history of the Communist Party, more than a billion people have gone to jail. Now, a lot of those were Xi Jinping’s rivals. So it was extremely convenient and strategic but it’s extraordinary how much popular goodwill he generated by doing that. And you would talk to ordinary people, even liberals, people who are critical of Xi Jinping politically who would say “Thank God, he’s doing something.”

SREENIVASAN: You mentioned that the Chinese government was at a point of losing hearts and minds. What does that mean?

LANGFITT: What that means is that people — the Chinese government isn’t really about much more than economic growth and power. And if you go back to the Mao era, there was ideology. But in order to save themselves, the Communist Party had to embrace market capitalism. Now, it’s more state capitalism. But the question is if you’re unelected and the reason you’re able to claim power is you won a civil war a long time ago and you’ve had a lot of growth but you never stood for election, you have to find some other way to hold people together. Corruption was really eroding that. And now, what we’re seeing from Xi Jinping is really a strong national sentiment. And what was very interesting in talking to some of the characters who in many ways were pretty liberal, fond and admiring of American principles of democracy and the constitution, checks and balances. They also, though, saw the United States as a bully. When they looked in the South China Sea, they felt the South China Sea really was China’s, that President Xi was right to build those islands and to try to push out the U.S. Navy. So they saw the U.S. as real bullies. They felt like they were surrounded. And I guess this gets at the nuance of Chinese today is they can see things from many angles. They read a great deal. They often — in most cases, they know more about America than Americans would know about China. And so even people who might be politically liberal still would be very supportive of President Xi because of the corruption, anti-corruption campaign but also because of this assertiveness abroad. It makes them feel better about China.

SREENIVASAN: So how does a person in China walking down the street perceive maybe this trade war? If you keep in touch with any of your contacts.

LANGFITT: I do.

SREENIVASAN: What do they think is going to happen? Do they think this is good? Or do they wrap themselves in flag of China?

LANGFITT: It’s the great thing about meeting all these different people is more and more now like the U.S., you get a wide variety of views. I think some people understand that the trade war is actually in some ways good for China. Interestingly enough. The argument being that President Trump is putting pressure on Xi Jinping and there’s more opportunities to maybe actually develop the economy better, make it more competitive. So it would be good for Chinese people but not good for the party. So the party controls all these state-owned enterprises. I mean it’s not like — remember that old expression? What’s good for General Motors is good for America.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

LANGFITT: Well, in this case, economic reform is not good for the party in certain ways. The party wants to keep control of them, a lot of state-owned enterprises for which it has a lot of power. It doesn’t want to privatize the whole system. That would actually create greater GDP, greater job growth and things like that but that’s not in the party’s interest. So there are some people not a majority at all who see Trump as something of a reformer. They may not like President Trump in any other way. Others, though, feel that he has — President Trump has overstepped his bounds by going after Huawei. Huawei is a terrific telecom company. When I was the Nairobi Bureau Chief of NPR, there was not very good Internet in Nairobi and I used Huawei USBs to run my bureau for a year. So I’m a fan of Huawei in that respect. And I think a lot of Chinese, particularly down in Shenzhen where Huawei and other big telecom companies, big tech companies are located feels that there’s sort of an unfair targeting of a company that is kind of a global leader from China.

SREENIVASAN: One of the characters that was interesting was that they had come to the United States and come back to China and they are kind of struggling with the sort of cultural question of where they are today versus where they grew up.

LANGFITT: Yes. This was a really interesting person that I got to know — he’s an investment banker. Her parents are in the Communist Party. They’re Communist Party officials. The corruption, the oppression she decided she wanted to leave China and start anew. And she got an MBA in the United States so she speaks very, very good English. She got to the United States and five months later, President Trump won the election. And she had been a great believer in democracy. And this began, she doesn’t like President Trump. She didn’t feel like a lot of voters had paid strict attention to what was going on and she began to become much more disillusioned about whether American democracy worked. And she started to see the Communist Party in a more positive way because she saw the efficiency, the economic growth, the ability to change things quickly without the messiness of democracy. And when she — it was interesting because I know when she went to America, she didn’t intend to return to China. And in the end, she moved back.

SREENIVASAN: OK. So now here she is back in China. Talk about the messiness of democracy. You’ve got protests in Hong Kong that have been happening every weekend over a specific issue but they’re gathering momentum. How does she think about that right at her doorstep so to speak?

LANGFITT: Well, she actually works in Hong Kong and she lives in Shenzhen, just across the border. She says if she were a Hong Kong person, she would be out there every night as well because she thinks that — from the perspective of a Hong Kong person, this is like a last stand against oppression coming and the creeping of authoritarianism from the Mainland. But I asked her about people in her offices. I was just talking to her this morning and she said a lot of Mainlanders that she works with don’t really have any sympathy for Hong Kong people. So it’s really interesting. Here, you have these democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong and many Mainlanders don’t really — they don’t care for Hong Kong people. There’s a real division between them. It goes back historically Mainlanders would go to Hong Kong in droves and buy up lots of products and bring them back to Mainland China because the products in Hong Kong were safe. There’s a huge problem with food safety and medical product safety in the Mainland and they drove up housing prices. So there’s a real kind of bitter division between Mainlanders and people in Hong Kong.

SREENIVASAN: When you talk about authoritarian sort of increases that China has made, one of the things that we at least see in the press is an increased surveillance state.

LANGFITT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: That there are a lot of people say it’s harder to get someone to talk now in China than it was five years ago.

LANGFITT: I think it is much more difficult for my colleagues now and my conversations with them doing what I was — what was much easier to do four or five years ago. Yes, I think it’s become the job is maybe more difficult now than since the Tiananmen crackdown.

SREENIVASAN: Why?

LANGFITT: I think the government realizes that it has a very sophisticated population, that has growing expectations that is well traveled. And it fears that if it allows people to be openly critical and to talk more that they’re basically it’s just going to erode their power. And I will say this when I came back in 2014, I started looking at Weibo, that is the Chinese equivalent of Twitter. And I was shocked at how open it was. I mean there were all kinds of criticism of the government and I sort of thought what kind of authoritarian state is this? Because if this goes on a lot longer, it clearly was going to erode the power of the government. So I think what they’ve done, what Xi Jinping has done is doubled down on oppression.

SREENIVASAN: Given that you have this cab out in public with these magnetic signs and you’re this white guy that’s driving this cab and there’s enough cameras around, there’s enough police around.

LANGFITT: Sure.

SREENIVASAN: Do the authorities know what you were doing? Were they concerned in any way?

LANGFITT: They definitely did because they can read the signs and I must have passed a ton of cops in Shanghai alone. I was never pulled over. And I thought I might be. Of course, I didn’t charge so I could never be – – I wasn’t breaking the law.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

LANGFITT: What I learned later, though, is that the Chinese Ministry of State Security obviously monitors foreign reporters. They sometimes read our stories. They sometimes interview people that we’ve talked to. I found out secondhand that one of the spies watching me had actually been listening to the stories. And he said I would like these stories. These are really good. He said I relate to some of these characters. I know some people just like this. So I don’t know for sure but it may be one reason that they didn’t bust me is because they thought the stories were pretty good.

SREENIVASAN: Frank Langfitt, the book is called “Shanghai Free Taxi.” Thanks so much for joining us.

LANGFITT: Thanks for having me, Hari.

About This Episode EXPAND

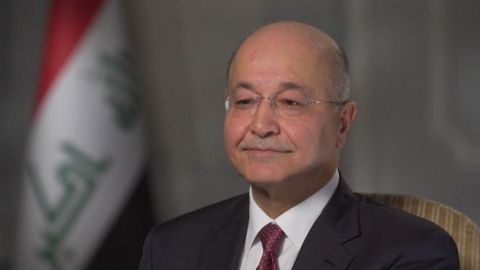

Christiane Amanpour speaks with Barhak Salih about Iraq’s relationship to tensions between Iran and the U.S. Warren Binford joins the program to discuss living conditions at an immigrant detention facility in Texas. Hari Sreenivasan speaks with Frank Langfitt, author of “The Shanghai Free Taxi.”

LEARN MORE