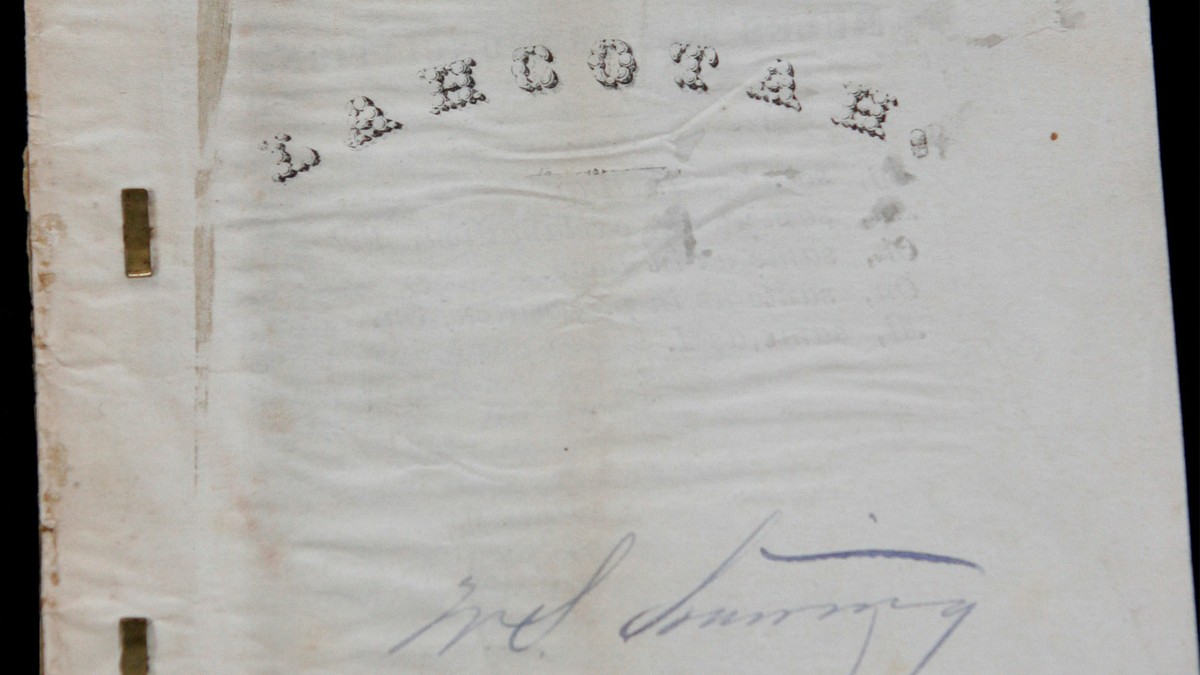

At the Tampa, Florida, ANTIQUES ROADSHOW, appraiser Thomas Lecky was handed a book in near-perfect condition called Lahcotah: Dictionary of the Sioux Language. The book, bound with staples, was written in December 1866 by army officers and Indian guides at Fort Laramie, an important stop on the Oregon Trail.

"This is the first book printed in Wyoming," Lecky, a rare-manuscript specialist, told the owner, who is the great-great-nephew of William Sylvanus Starring, one of the book's authors.

But could Lecky make such a definitive statement?

"In our field, we're lucky," Lecky says, "because people often put together bibliographies of rare books." These catalogs document when, where, and how many rare books in a place or genre were printed. All the sources that Lecky turned to confirmed what he suspected: the book brought to him in Tampa was rare indeed.

Lecky began with the bibliography Wyoming Territorial Imprints by Christine Stopka, published in 1990, which confirmed that the earliest book printed in the Dakota territories which included what is today Wyoming—was the Lakota dictionary. The book was so rare that J.C. Pilling, the author of the Proof-Sheets of a Bibliography of the Languages of the North American Indians, an 1885 bibliography that Thomas checked, couldn't locate a copy. Pilling, though, was later given the book and pasted a note in it that reads, "Present from Gen. Starring... Big find. 50 copies only Starring thinks." Thomas was curious about how many copies still existed, so he got online and searched the Union catalog, which lists library holdings owned by universities or historical societies. The catalog showed only nine copies. And the book American Book Prices Current revealed that only one copy of the dictionary has been auctioned in the last 30 years.

"This was a how-to guide, printed on an army press, a way to communicate with Sioux on the plains," Thomas says. "After its usefulness, it was probably thrown away." What makes this item so special, Thomas believes, is not just its significance as the first book printed on the frontier or its excellent condition, but rather its historical context. The dictionary was written at Fort Laramie, a fur trading post that evolved into a military fort that protected white settlers heading to the West Coast after the California gold rush in the late 1840s. These settlers, who devastated the buffalo herds, were unwelcome by the Plains Indians. The dictionary was printed at the height of the Indian wars on the plains, and Starring was working on it during the brutal winter of 1865-1866, when many Plains Indians perished, in part because white settlers had denied them blankets, food, and other rations.

Starring's dictionary was useful to the army officers and others, and the author's numerous hand-written notes show his desire — perhaps fueled by pressure from authorities — to make his dictionary as accurate as possible. The book brought to the ROADSHOW includes 20 hand-written words that Starring added to the more than 1,000 printed dictionary entries, including "boy," "buffalo robe," "raisin," "snake," "butter," "to play a game at cards," "coffee," "to come," "man" (Indian), and "man" (white). Starring also scribbled in conjugations of the word "to want."

Incidentally, the owner of the Lakota dictionary had also brought with him two metal pendants that Thomas referred to on-air as "gorgets" — a term that can apply to various types of ornaments worn around the neck, in some cases deriving from leather or metal pieces whose original purpose was to protect the throat during battle. In this case, Thomas explains, the pendants are actually of a certain "cloud-shaped" kind known as "pectorals" (the two metal objects pictured in the collection), which were especially preferred by many of the Plains Indians. "These happened to be owned by two extremely important Sioux chiefs," Thomas explained to the pendants' owner. "One was owned by Red Cloud, and the other by Spotted Tail."

Thomas speculates the pectorals were given to Starring during the spring and fall of 1866, when war chiefs Red Cloud, Spotted Tail, Standing Elk, Dull Knife, and others went to Fort Laramie to negotiate a treaty with government officials. Because of his knowledge of the Lakota language, Starring might have been asked to be present at the negotiations as a translator and might have received the two pectorals as a reward for his efforts.

Thomas estimated that the pectorals were worth $8,000 to $12,000 each, and he put the dictionary's value between $60,000 to $80,000, for a total value of $76,000 to $104,000. How close did the Christie's auction of the book and the pectorals on December 15, 2005, come to that estimate? They sold for $88,500, what Thomas referred to as "a very happy end to the story."

Related

This account was largely based on the description of the Lakota objects written by Thomas Lecky for the December 15, 2005, books and manuscript auction at Christie's.