“An Unusual Situation”: Experts Weigh in on Trump’s National Emergency Declaration

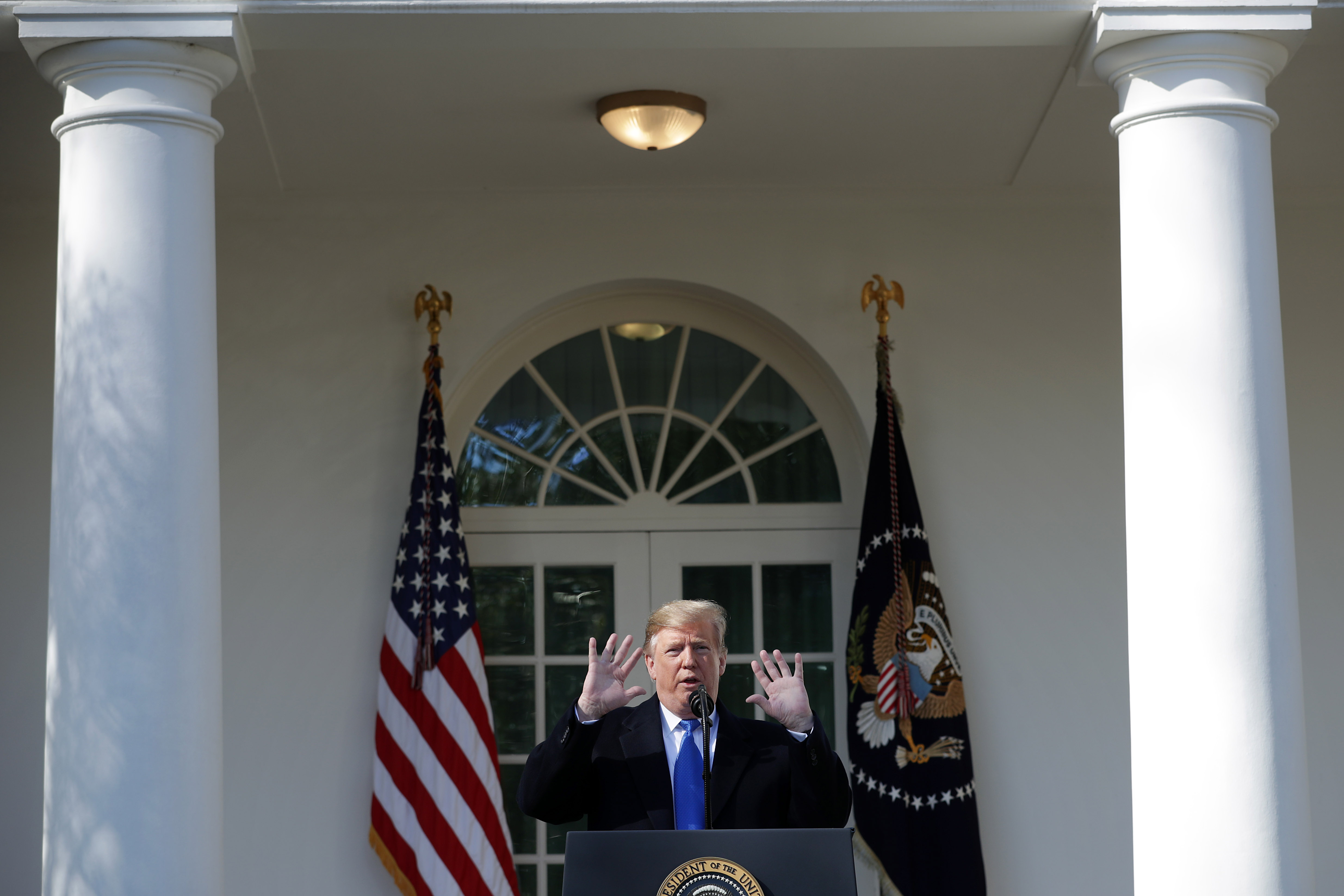

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks on border security during a Rose Garden event at the White House February 15, 2019 in Washington, DC. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

After weeks of sparring with Congress, President Donald Trump invoked a national emergency Friday in an attempt to secure money for a barrier along the United States’ border with Mexico. The declaration came a day after the passage of a bipartisan spending bill that caps funding for the wall, a key Trump campaign promise, at just under $1.4 billion.

“We’re going to be signing today and registering [a] national emergency and it’s a great thing to do because we have an invasion of drugs, invasion of gangs, invasion of people, and it’s unacceptable,” Trump said during a speech in the White House Rose Garden on Friday morning. “We have a chance of getting close to $8 billion — whether it’s $8 billion or $2 billion or $1.5 billion — it’s going to build a lot of wall, we’re getting it done.”

Trump has hinted at the possibility of declaring a national emergency since the 35-day partial government shutdown — which was triggered by border wall funding disputes — that ended January 25. During Friday’s announcement, he referenced national emergency declarations from previous presidents, noting that they stirred little controversy. “I’m going to be signing a national emergency and it’s been signed many times before. It’s been signed by other presidents,” he said. “There’s rarely been a problem. They sign it, nobody cares.”

The National Emergencies Act, which was passed in 1976, was originally intended to put a check on presidential powers by limiting a federal law that granted emergency executive authority. The act does not confer any power inherently, but allows presidents to make use of other laws in times of national emergency. For example, it allows the president to use the International Emergency Economic Powers Act to put economic sanctions on foreign individuals and entities deemed an “unusual and extraordinary threat.”

The Brennan Center for Justice out of New York University Law School tracks national emergencies declared over the past four decades. More than 30 are technically ongoing. Presidents have used the law to enact economic sanctions, to target terrorism — even to fight the flu. “They’ve declared emergencies in situations where probably most people would agree one existed: The H1N1 virus or the Iranian hostage situation 1979,” said Chris Edelson, author of “Emergency Presidential Power: From the Drafting of the Constitution to the War on Terror” and an assistant professor of government at American University.

But experts told FRONTLINE that Trump is employing the act in unprecedented ways.

“What the president is doing here is invoking this … supposed emergency power simply as a means of circumventing checks and balances and separation of powers,” said Northwestern University law and public policy professor Martin Redish. “That’s never been the way this act has been used before.”

Trump seemed to cite a declaration made by President Obama on Friday, telling reporters, “We may be using one of the national emergencies that [Obama] signed having to do with cartels, criminal cartels.” Obama’s 2011 declaration targeted the financing of conflict and crime, freezing assets associated with global crime organizations the Yakuza, Los Zetas, the Camorra and the Brothers’ Circle.

But declarations like Obama’s have not been wielded as a means to skirt Congress over funding disputes.

“This is an unusual situation … because here a president asked for something and Congress said no, essentially, and now he’s going to declare an emergency to do what he couldn’t get Congress to do,” said Harvard Law professor Mark Tushnet. “That is new.”

Edelson agrees. “This is different than what Obama, or Bush or other presidents have done because it’s clearly an attempt to get around Congress’ intent,” he said. “There’s nothing that President Obama or President George W. Bush or any president since 1976 has done like this, when Congress has quite clearly said, ‘We’re not giving you money,’ and the president says, ‘Well, I’ll find a way around that.’ There’s just no precedent for that.”

Democratic Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Joaquin Castro announced that they plan to introduce a bill to stop the declaration. But even if it passes, it would require the president’s signature to go into effect. Overriding a presidential veto requires a two-thirds majority in both the Democratic-led House and Republican-led Senate, which could present a stumbling block for Trump challengers.

Still, lawmakers expressed concern that the emergency declaration could have far-reaching effects. In a joint statement Friday, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer said that “Congress cannot let the President shred the Constitution.”

Meanwhile, Republican Sen. Susan Collins called the move “a mistake.”

“I don’t believe that the National Emergencies Act contemplates a President unilaterally reallocating billions of dollars, already designated for specific purposes, outside of the normal appropriations process,” she said in a statement Thursday. “It also sets a bad precedent for future Presidents — both Democratic and Republican — who might seek to use this same maneuver to circumvent Congress to advance their policy goals. It is also of dubious constitutionality, and it will almost certainly be challenged in the courts.”

The president made it clear Friday morning that his administration expects and is prepared for a court battle over the emergency declaration.

“They will sue us in the ninth circuit … and we will possibly get a bad ruling, and then we’ll get another bad ruling, and then we’ll end up in the Supreme Court and hopefully we’ll get a fair shake, and we’ll win in the Supreme Court, just like the ban,” Trump said, referencing his controversial proclamation banning travel from majority Muslim countries.

Hours later, the ACLU announced that it planned to sue the president.