Blood and Soil

Travel to the rural South as Elder Burch, Charley Patton and others record early Delta blues, gospel and protest songs. The Great Flood of 1927 devastates Mississippi River communities, leading to northern migration and Chicago Blues by Howlin’ Wolf.

Read Full Transcript

Robert Redford: In the 1920s, record companies went out into America and for the first time recorded the music of everyday working people.

They traveled to remote regions, auditioned thousands of everyday Americans, and issued their music on phonograph records.

Some of those artists, like the Carter Family and the Memphis Jug Band, became popular stars and are remembered as pioneers of blues, country, and R&B.

Others are remembered only as names on old record labels.

[Sister Rosetta Tharpe's 'Up Above My Head' playing] ♪ Up above my head ♪ I hear music in the air ♪ Up above my head ♪ There is music in the air ♪ Up above my head ♪ Music in the air ♪ And I really do believe, really do believe ♪ ♪ Joy's somewhere ♪ All in my room ♪ Music everywhere ♪ All in my home ♪ Music in the air ♪ Up above my head ♪ There is music in the air ♪ And I do believe, I do believe ♪ ♪ Joy's somewhere ♪ Well, well, well, up above my head ♪ ♪ Thank God almighty, music everywhere ♪ ♪ Music everywhere ♪ Up above my head ♪ Don't you know, music in the air ♪ ♪ Up above my head ♪ There is music in the air ♪ You know, I really do believe ♪ ♪ I really do believe ♪ Joy's somewhere ♪ Yes, in the city... Redford: African-American spirituals and gospel have shaped every style of American music.

In the 1920s, the first wave of black recording stars included dozens of religious singers and fiery preachers, who inspired listeners to uplift their spirit and find freedom in song.

One of these pastors was an obscure figure named Elder Burch, who brought his church choir to Atlanta in 1927 and in a single session recorded 9 passionate sermons and one haunting hymn.

Woman: ♪ Ever since my sin Choir: ♪ Ever since my sin ♪ ♪ Been taken away ♪ Been taken away ♪ My heart keeps singing All: ♪ Singing, singing, Lord, all the time ♪ Woman: ♪ Since Jesus washed ♪ Since Jesus washed ♪ ♪ Me in his blood ♪ Me in his blood ♪ My heart keeps singing All: ♪ Singing, singing all the time ♪ Woman: ♪ I'm sanctified ♪ I'm sanctified ♪ By the Holy Ghost ♪ By the Holy Ghost ♪ My heart keeps ringing All: ♪ Singing, singing all the time ♪ Woman: ♪ Since Jesus washed ♪ Since Jesus washed ♪ ♪ Me in his blood ♪ Me in his blood ♪ My heart keeps singing All: ♪ Singing, singing ♪ Lord, all the time Amen! Jesus. Lord God Jesus.

Redford: The power of those voices captured our imagination... and set us on a quest to solve the mystery.

Who was Elder Burch?

Our first stop was the current home of Victor Records, the basement of the Sony Building in New York City.

Bernard MacMahon: We just wanted to try and find anything about Elder Burch.

We knew he'd been recorded by Victor, so Sony, who own that label, allowed me to come down to this basement here and look through their records, which have every Victor recording from the turn of the last century to the present day, and these are the sheets that the recording engineers would type up, listing what songs were played, what instruments were used.

You can see here Edith Piaf, Elvis Presley.

I mean, every act you can think of.

Here it is, 'Bu,' and in it, the folders are filled with these smaller brown folders.

Julie Budd, whoever she was.

The Buffalo Bills.

Bumble Bee Slim.

The Bummers.

Here he is. Elder J.E. Burch.

Here's the original sheet from 1927 that was recorded when Ralph Peer went to Atlanta, Georgia, to make this record.

So this is the actual thing that was in the engineer's typewriter the day of that recording session, and these are all the songs that Burch recorded on this day.

Look at the number of them here.

Address-- Cheraw, South Carolina.

Maybe that's where he was from.

Redford: So we traveled to a town we had never heard of, known as the prettiest town in Dixie.

It was springtime as we drove through Cheraw with its historic old houses and quiet roads dappled with blossoming trees.

Apparently, little had changed over the past century.

We talked to many people in Cheraw, but none of them remembered Elder Burch.

Eventually, we were told to cross the tracks and visit one of the town's elders--Ted Bradley.

Ahh. Ahh.

How did you do-- how did you do this?

Redford: We asked Ted Bradley if he recognized Elder Burch in this newly discovered photograph.

Bradley: Oh, man. Mmm.

Man, you know how long that's been?

That was 70 years ago.

Ha ha ha!

70 years ago.

Very few people know anything about Elder Burch, very few people.

He was a tall, uh, good-looking man, I would say, and he would stand there kind of rocking with spats on his shoes, shoes always shined.

He was well-dressed-- vests, gold chains.

Burch: ♪ I'm gonna sing [With choir] ♪ So God can use me ♪ Right down here in this world ♪ ♪ I'm gonna sing so God can use me ♪ ♪ Right down here, Lord, in this world... ♪ Bradley: Oh, he could talk that wonderful 'Hey. How you boys doing today?'

He had that eloquent way of speaking to you, you know.

Burch and choir: ♪ I'm gonna sing so God can use me ♪ ♪ Right down here, Lord, in this world ♪ ♪ I'm gonna moan so God can use me ♪ Bradley: He was just a wonderful, good-looking man, and I just wanted to be like him.

Ha ha ha!

Nine-year-old boy wanting to be like that man.

Ha ha ha! Ha ha ha!

Can you imagine that? Ha!

Redford: We discovered Elder Burch was born in 1876 just outside Cheraw.

He became a turpentine harvester, traveling to Mississippi, where he became a minister and a disciple of E.D. Smith, founder of the Triumph Church movement, whose congregations channel the word of God in a rapturous frenzy known as speaking in tongues.

When Burch returned to Cheraw, he bought land and opened a store, a boarding house, a barber shop, and a restaurant, all remarkable achievements for an African-American in the South at that time.

In 1924, he built a church in Cheraw with his own hands, gathered a fervent congregation, and formed a thunderous choir.

[Choir singing indistinctly] Redford: We find the Triumph Church still standing and meet Elder Burch's modern successor, Pastor Donnie Chapman.

Chapman: In the twenties, Triumph Church, church in general, period, was everything because everything was segregated and, um, the blacks went to their churches, the whites went to their churches, and black people back in that day didn't have much.

The only thing that they had was--by the church was hope for the future, hoping that there would be a better day coming than what they were experiencing at that very present time.

Elder Burch really did a very important thing for Cheraw.

He started their local branch of the NAACP with Mr. Levi Byrd... and every day, they put their life on the line for the black community, and Elder Burch tried to make this world a better place for all of us to live.

In the name of the Lord Jesus Christ, our savior, who came, suffered, and died to save us from all our sins.

Congregants: Amen!

Redford: Charismatic preachers like Elder Burch rose up at a time when popular movements for civil rights were spreading across the South.

Congregation: ♪ Lord God Jesus Redford: Triumph and the other African-American churches were at the heart of the struggle for equal rights, dignity, and self-respect, and music became a vehicle for liberation.

Congregation: ♪ Sound for days ♪ And Delilah... Bradley: We sang those old gospel songs to get relief from the burdens of the day from the cotton fields, from cropping tobacco, from all of those hard tasks, and when you hear one singing a song across the field that the whole field take it up.

It would go across the field just like a wave, you know.

♪ Amazing grace Then you'd hear it pick up on the other side.

♪ How sweet Then after they sang it, they'd hum.

[Hums] And that just makes you just forget about that hot sun on your back.

Ha ha ha!

Down on your knees in that 85-degree weather, picking that cotton.

[People humming] Redford: At the Triumph Church, we find another of the town's elders.

Man: When the Triumph Church started their services on Sunday nights--Sunday nights was their big service time-- you could hear it a number of blocks away.

Elder Burch was just one of those people that attracted people because of the music that he played, and a lot of people would go by just to see people be really spiritually moved and dance or shout in the church, and we would just listen to the singing, the music, and it was a joyous ceremony.

Man: A lot of people looked down on the Sanctified Church because they just was getting loose, and you could hear the sensuality and the fervor, you know, happening in what they were doing.

They wanted those churches to be more, you know, staid and, uh, steady, you know, and, you know, it's like, 'Well, yeah, but boring.'

Burch and choir: ♪ Yes, love is my wonderful song ♪ ♪ I'm singing it all day long ♪ ♪ Since the Spirit came in ♪ And has banished my sin ♪ Yes, love is my wonderful song ♪ Bradley: When night come and during the service, all of those people would come so they could hear that music, hear that singing, hear that stomping, hear those people in there jumping and praising the Lord and--ha ha--having a wonderful time up in there.

Burch and choir: ♪ Yes, love is my wonderful song ♪ ♪ I'm singing it all day long Redford: The fervor of Elder Burch's congregation inspired local youngsters, and surprisingly, we discovered that one of these youngsters became a giant of modern jazz.

Gillespie: You know who lived next door to Elder Burch's church?

My cousin, Dizzy Gillespie.

[Dizzy Gillespie and orchestra playing 'Salt Peanuts'] Let me read you this out of Dizzy's autobiography.

'Like most black musicians, much of my early inspiration, 'especially with rhythm and harmonies, 'came from the church.

'The Sanctified Church stood down the street from us.

'The leader of the church's name was Elder Burch, 'and he had several sons.

'Johnny played the snare drum.

'His brother Willie beat the cymbal.

'Another one of the Burch brothers 'played bass drum.

'They used to keep at least 4 rhythms going, 'and as the congregation joined in, 'the number of rhythms would increase 'with foot stomping, hand clapping, 'and people catching the spirit 'and jumping up and down on the wooden floor, 'which also resounded like a drum.

'Even white people would come down and sit outside 'in their cars just to listen to the people 'getting the spirit inside.

'Everyone would be shouting and fainting and stomping.

'The Sanctified Church's rhythm got to me 'as it did anyone who came near the place.

'People like Aretha Franklin and James Brown owe everything to that sanctified beat.'

Owww!

♪ Baby Gillespie: 'I received my first experience with rhythm 'and spiritual transport going down there 'to Elder Burch's church every Sunday, and I've just followed it ever since.'

♪ Oop bop sh'bam ♪ Coo coo bop Bradley: If you listen to Dizz's music, you hear Triumph.

♪ ...Coo coo bop... They lived right up the street from the church, and he heard every note, every downbeat, every drumbeat.

He could hear it from his bed.

Gillespie: If you walk up the street from Elder Burch's church a few houses, you will arrive to where Dizzy lived.

['Oop Bop Sh'bam' continues] They made it into a park now.

In the Dizzy Gillespie park, you can still hear the music from Elder Burch's church.

[Distant choir singing] This record recorded in the twenties by Elder Burch influenced so many people around Cheraw, and it's just amazing to see the members of the Triumph Church Choir, composed of people throughout the United States, arriving here in Cheraw to sing all in tribute to Elder Burch.

Chapman: We would like to welcome you to our wonderful city of Cheraw, South Carolina, to a church that Elder John Burch built back in the 1920s.

Amen. Amen.

You know, in 'Psalms' 1:49, it says, 'Sing a new song unto the Lord.

Sing a new song,' and that song that he sung I will sing unto the Lord.

My heart just keeps right on singing and praising almighty God.

Amen. All right.

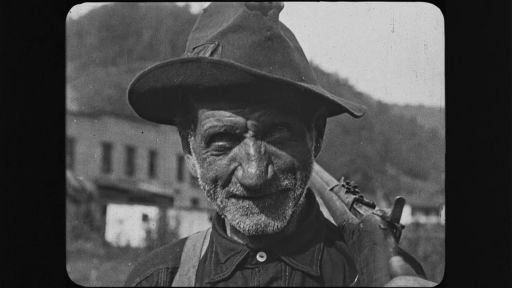

[Applause] Man: ♪ I'm sanctified Choir: ♪ I'm sanctified ♪ With the Holy Ghost ♪ With the Holy Ghost ♪ ♪ My heart keeps ♪ Singing, singing, singing ♪ ♪ All the time [Drums, organ, and bass playing] ♪ I'm singing ♪ I'm singing ♪ Yes, far from freedom ♪ I'm singing ♪ He lifted me up ♪ I'm singing ♪ I'm singing ♪ I'm singing ♪ Singing ♪ Oh, oh, oh ♪ Singing ♪ All the time ♪ I'm singing ♪ 'Cause he brought me out ♪ ♪ I'm singing ♪ I'm gonna sing my song ♪ I'm singing ♪ I'm gonna sing my song, now ♪ ♪ And I'm gonna sing, I'm gonna sing, I'm gonna sing ♪ ♪ I'm singing ♪ Oh, yes, I'm singing ♪ I'm singing ♪ Can't you help me sing? ♪ ♪ I'm singing ♪ Unto His name ♪ I'm singing ♪ I'm singing for God ♪ Oh, oh, oh, oh ♪ Singing ♪ All the time ♪ Time [Cheering] [Drums, organ, and bass playing] Dick Justice: ♪ Get down, get down ♪ Little Henry Lee ♪ And stay all night with me ♪ The very best lodging I can afford ♪ ♪ Will be far better than thee ♪ ♪ I can't get down, and I won't get down ♪ ♪ And stay all night with thee ♪ ♪ For the girl I have in that merry green land ♪ ♪ I love far better than thee... ♪ Redford: Some of the most striking music of the early recording era came from the coal mines of Logan County, West Virginia.

These gritty songs capture stories of hard lives, hard deaths, hard luck, and hard labor.

The men of Logan County spent their days underground, scratching a living out of solid rock.

Three of them were also exceptional musicians-- Frank Hutchison, Dick Justice, and Ervin Williamson.

Bill Williamson: My father was a musician, Ervin Williamson, who founded the group the Williamson Brothers and Curry back in the twenties.

They were very, very good, and they had a good following, but he chose to come to Logan County and have a family and to work in the coal mines and make money that way.

They went in the coal mines at daylight, and they didn't get out till after dark, and I remember my dad telling me that they hand-loaded coal with a shovel, and they got paid 50 cents a carload, and the only people who prospered and--and got better off was the coal companies themself.

That's--that's the way my dad told me the way it was, you know?

My name is Eugene Justice.

My father was Dick Justice.

Dad worked in the coal mines all of his life.

From what I heard, he started, like, when he was 13 years old.

One time, Dad took me down in one maybe two miles, and I didn't want no more.

I said, 'Get me back out of here.'

It was a eerie feeling, man, all that dirt over our head.

Dick Justice: ♪ Old black dog, when I'm gone, Lord, Lord ♪ ♪ Old black dog, when I'm gone ♪ ♪ When I come back with a $10 bill ♪ ♪ And it's 'Honey, where you been so long?' ♪ Bill: It was dangerous just to go in, let alone work in it, you know?

There was a lot of mining accidents back then.

My dad told me every time you'd go down at that time, you're just taking your life in your own hands.

Eugene: Dad--he'd work all week, and on the weekends, he'd have his beer and he'd play his guitar.

It was just to get together and play their instruments.

Bill: Dad loved music, and people done it a lot back then like a hobby.

They just had the music in them, and they enjoyed it.

They didn't plan on making a career or making big-time money like they do now with music.

It was just something that neighbors and people got together and they done, but that's the way it was.

That's the way life was back then.

Eugene: It was pretty rough on people working in the coal mines, half killing theirself and the coal companies taking most of their money back.

That's what Dad did.

Every penny he got went right back to them.

Bill: Back in 1921, miners started marching, and they was trying to get unions for them.

Coal companies didn't want the union to come in because if they did, that'd mean that the coal miners would get better pay and everything.

Well, the sheriff back at the time, he had a army of deputies to meet him at the top of Blair Mountain.

They had guns all over the place, you know.

Of course, the coal miners, they were armed, too, but they were outnumbered by 5 or 10 to 1, and several people were killed.

It's believed that some people's remains might still be laying on the mountain up there.

Redford: The mine wars and the hellish working conditions inspired the Logan musicians to find a way out through music.

Williamson: Back then, Dick Justice and Frank Hutchison, they were very good, and they all knew each other.

They--they played music together many a time.

Hutchison: ♪ Stackalee, oh, Stackalee ♪ ♪ Please don't take my life ♪ I've got 3 little children ♪ And a weeping, loving wife ♪ ♪ You're a bad man ♪ Bad man, Stackalee... Redford: Frank Hutchison was the first Logan County artist to make a record.

He traveled to New York in 1926 to record for the Okeh company, and when they invited him to another session in 1927, he arranged for some friends to secretly audition on their lunch break.

Now, when Dad made some recordings, Frank Hutchison and them, they helped him set up an audition, and they auditioned over the telephone.

Redford: The Okeh scouts liked what they heard, and they wired the Williamson Brothers and Curry train fare to come record in St. Louis.

Bill: Dad and Uncle Arnold, they went on down on the train, and they recorded 6 songs, and--and one thing about when you made recordings back then, you recorded one time.

You didn't get that Take 1 and Take 2 and Take 3 and Take 4 until you got it right.

Whatever happened on the first recording, that is what went out.

♪ I'm going down this road feeling bad ♪ ♪ Oh, I'm going down this road feeling bad ♪ ♪ Oh, I'm going down this road feeling bad ♪ ♪ Lord, Lord ♪ And I ain't gonna be treated this a-way ♪ ♪ I'm going if I never come back ♪ ♪ Oh, I'm going if I never come back ♪ ♪ Oh, I'm going if I never come back ♪ ♪ Lord, Lord ♪ And I ain't gonna be treated this a-way ♪ Bill: They recorded 6 songs, and they got paid $25 a song, and that was all, no royalties or anything.

They just got paid $25 a song, and that was it.

That's a lot different than getting paid 50 cents a coal car, you know?

Redford: Dick Justice was the third Logan mineworker to win a recording contract.

Brunswick Records paid his fare to Chicago to record in their brand-new studio on the 21st floor of the American Furniture Mart.

Justice: ♪ Some take him by his lily-white hand ♪ ♪ Some take him by his feet ♪ We'll throw him in this deep, deep well ♪ ♪ More than one hundred feet ♪ Lie there, lie there, loving Henry Lee ♪ ♪ Till the flesh drops from your bones ♪ ♪ I'd fly away to the merry green land ♪ ♪ And tell what I have seen Redford: After his recording session, Dick Justice returned to the mines and waited for a phone call that never came.

He never spoke a word about his recordings, even to his own son.

He--he never talked about it.

I never heard him--mentioned ever recording songs.

I--you would think if he recorded songs at one time or another, I would have heard him sing one of them.

I never did.

Redford: The Logan musicians received little recognition for their records, but decades later, 3 of their songs were revived on 'The Anthology of American Folk Music,' an album that became the Bible for a new generation of musicians.

['Henry Lee' playing softly] 'The Anthology' opened with Dick Justice's 'Henry Lee' and included Frank Hutchison's 'Stackalee' and the Williamson Brothers' 'Gonna Die With a Hammer In My Hand.'

Bill: I'm holding in my hand here one of the original old 78 records, 'Gonna Die With My Hammer In My Hand.'

That was a story about John Henry.

Companies at that time, they brought in a steam machine to beat the steel and to whup it in the ground is what they called it, but John Henry, according to this legend, he was not gonna be beaten by a steam machine.

He could outdo it, and he just worked so hard trying to beat the steam machine that he just laid down his hammer and died.

['Gonna Die With a Hammer In My Hand' playing] ♪ John Henry told his captain ♪ Man ain't nothing but a man ♪ Before I'd be beaten by this old steam drill ♪ ♪ Lord, I'll die with my hammer in my hand ♪ ♪ Lord, Lord ♪ Lord, I'll die with that hammer in my hand ♪ Bill: I can listen to his songs and get them on the computer, on YouTube, and I listen to them sometimes, and it--and it chokes me up because I know what it would do for him.

He wouldn't know--he wouldn't know what to think about it.

He would--it would-- it would just be amazing to him, you know, that his music was being recognized and him being gone since 1972, and I--he--he would have really been overwhelmed with it.

He really would have.

Bruce Springsteen: 1, 2, 1, 2, 3!

♪ John Henry, well, he told his captain ♪ ♪ Captain, a man, he ain't nothing but a man ♪ ♪ Before I let your steam drill beat me down ♪ ♪ I'm gonna die with a hammer in my hand, Lord, Lord ♪ ♪ I'll die with a hammer in my hand ♪ Come on!

[The Rolling Stones' 'Little Red Rooster' playing] [Crowd cheering] ♪ I am the little red rooster, baby ♪ [Cheering] ♪ Too lazy to crow today [Cheering] Jack Good: I was in Chicago a little while ago, and I found a chap singing the blues, and it turned out to be somebody you know about.

Uh, in fact, he's quite famous, isn't he, in Britain?

Yes. Well, he was the first one that recorded 'Little Red Rooster.'

Was he? Yes.

When did he--tell us something about him, Brian.

Well, when we first started playing together, we started playing because we wanted to play rhythm and blues, and Howlin' Wolf was one of our greatest idols, and so I think it's about time you shut up and we had Howlin' Wolf onstage.

Yeah, I agree. OK.

Let's get him on. Howlin' Wolf.

♪ When I was doing right ♪ You couldn't believe a word I say ♪ ♪ When I was doing right ♪ You couldn't believe a word I say ♪ ♪ You think I'm crazy ♪ But I can't let you have your way ♪ How I done started to make records?

I was plowing, plowing 4 mules on the plantation, and a man come through there picking a guitar called Charley Patton, and I liked his sounds.

Every night that I'd get off of work, I'd go over to his house, and he'd learn me how to pick the guitar.

Then I went to playing from there.

[Charley Patton's 'Mississippi Boweavil Blues' playing] ♪ Sees a little boweavil ♪ Keeps moving in the, in the ♪ ♪ Lordie ♪ You can plant your cotton ♪ And you won't get a half a bale, Lordie ♪ ♪ Bo weevil, weevil ♪ Where's your native home, Lordie? ♪ ♪ Bo weevil meet his wife ♪ 'We can sit down on the hill,' Lordie ♪ ♪ Bo weevil told his wife ♪ 'Let's trade this 40 in,' Lordie ♪ ♪ Boweavil, boweavil ♪ 'Ought to treat me fair,' Lordie ♪ ♪ Next time I need you ♪ Have your family there, Lordie ♪ Redford: Patton was a mythic figure, and his first 3 records were released under 3 different names-- Charley Patton, Elder J.J. Hadley, and the Masked Marvel.

There is no film footage of him and only one known photograph.

Patton lived in a plantation culture that had hardly changed since the 19th century, but a music store owner named H.C. Speir in Jackson, Mississippi, was excited by Patton's raw sound and cut an audition record in his makeshift recording studio.

Uh, this is H.C. Speir.

I opened up the first recording session for making trial records.

That was in 1926, and I made a test for--for Patton.

Patton was good.

As a rule, the best talent for the blues singing came from the Mississippi Delta, and that due to hard times, and that gave them more incentive to put more into blues, you see?

In other words, if you were sitting around at night and hear a owl sing, then you would kind of feel lonesome, and when they would sing late in the evening, why, it--it was a lonesome sound, too.

That--that's what made those records sell better, too, but, uh, of course I would say Charley Patton was one of the best talents I ever had, and he was one of the best sellers on record.

Redford: Charley Patton's songs were often intensely personal, reflecting the harsh realities of his life.

In 'High Water Everywhere,' he recalls the devastation of the great Mississippi flood in 1927.

♪ Then high water was rising ♪ And flooding was all around Water is all around.

♪ It was 50 men and children ♪ Come to sink and drown ♪ Well, ohh, ohh, Lordie ♪ Women and grown men drownin' ♪ Ohh ♪ Women and children taken down ♪ Lord have mercy, honey.

♪ I couldn't see nobody at home ♪ ♪ And wasn't no one to be found ♪ Phew.

Well, the significance of Charley Patton cannot be understated.

Charley was just a force of nature.

Incredible voice, and if you listen to the music, it always has that lope, you know?

You know, you look at-- you look at some of these guys, and you go, like, 'OK. So what does this guy do all day long?'

All day long, he's got two mules, and they're just going up and down the field plowing.

That was the only way they did it.

Didn't have a tractor, and all of that's in the music.

Patton: ♪ I'm going away ♪ To the world unknown ♪ I'm going away ♪ To the world unknown ♪ I'm worried now ♪ But I won't be worried long ♪ My rider got something ♪ She trying to keep it hid... Redford: Charley Patton lived on a vast plantation known as Dockery Farms.

Like many black Delta dwellers, his family would later leave for the North, but we brought two young relatives back to explore their roots.

It was the first time they had visited Dockery.

My grandfather, John Cannon, was born on this plantation and told me that 'I have a very famous uncle who invented blues.'

My Aunt Bessie would say that Charley Patton was the ultimate showman.

I'll say it like she said it.

'He could pick the guitar,' uh, with his mouth, with his hands, behind his back, um, crawling, lying on the floor, um, simulating different acts onstage.

He was like a one-man band.

To come here to Dockery and look around is a very humbling experience.

To know that a woman that I know and love as a child picked cotton on this plantation, to know that there were thousands of African Americans enslaved against their will, sharecropping for a meager existence, I get new insight, and I'm really grateful for the struggles and the sacrifice that my ancestors made, uh, before me.

My name is William Lester.

I moved here over 40 years ago, and I'm the executive director of the Dockery Farms foundation, and, uh, I am just tickled pink for you to be here and, uh, for me to get to meet you because I had no idea when I started my career that Charley Patton would be so important to me.

At the turn of the century, all the workers built a 12-mile-long railroad from Dockery all the way to Boyle, and so that train brought all that food here and kept those people alive, but what it did was, it brought all the blues singers here.

And back then, they had no fans, no electricity, no running water, no nothing, and so they wouldn't have heard anything all week long while they were working except maybe the wind in the leaves, and all of a sudden, these guys would show up, they'd come in on the train.

Can you imagine what that did to them?

They'd been working so hard all week long, and 'Wow!'

People would show up playing metal acoustic National guitars, loud and brassy.

[Playing 'Death Letter Blues'] ♪ He got a letter this morning ♪ ♪ How y'all reckon it read?

♪ Said, 'Hurry, hurry' ♪ 'The gal you love is dead' ♪ He got a letter this morning ♪ How y'all reckon it read?

♪ It said, 'Hurry, hurry' ♪ 'Because the gal you love is dead' ♪ ♪ Well, he grabbed up his suitcase ♪ ♪ Took off down the road ♪ When he got there, she was laying ♪ ♪ On the cooling board ♪ He grabbed his suitcase ♪ Ah, and took off down the road... ♪ Lester: This Dockery commissary that we're sitting in front of drew a lot of people like Son House.

All kinds of blues singers, almost all of them, back in the twenties and thirties came here because of the isolated group of people, and they could perform in front of them, so they had a-- a captive audience, almost.

Mm-hmm.

Kenny: In that era, reality was you're a sharecropper, you're working hard every day of your life, and music was a break from reality, a break from that hard day-to-day work.

The reason Dockery is considered to be the birthplace of the blues is because of all the education that went on here.

Howlin' Wolf came here as about a 10 year old, and, you know, I mean Howlin' Wolf's a big bluesman.

Well, he couldn't do anything when he came here with a guitar.

Charley taught him how to play the guitar.

When he was about 18, he left.

At the same time, Pops Staples came here... Tracy: Sure.

Tommy Johnson, uh, Son House came here, Robert Johnson came here, and he's considered the best guitar player of the blues, but they all learned here from Charley, and Honeyboy Edwards played here.

He was probably one of the last original blues singers to actually play here at Dockery.

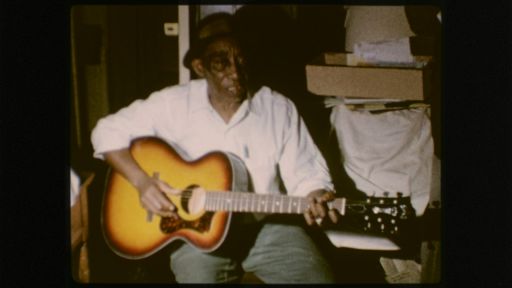

Redford: This previously unseen footage includes the earliest filmed performance by a Dockery musician-- Honeyboy Edwards playing on a street corner in 1942.

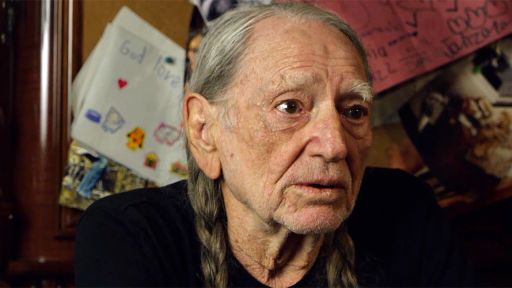

♪ Lord, do you hear me when I'm down? ♪ ♪ I'll be the same way when I ride ♪ ♪ 'Cause I see my woman, baby ♪ Lord, she standing on the other side ♪ ♪ Lord, I'm gonna walk to New York City, baby, now ♪ ♪ See that Gulf of Mexico Redford: When we interviewed Honeyboy, he was 91 years old, one of the last musicians with direct links to Charley Patton.

This is Honeyboy Edwards, and I was born in Shaw, Mississippi, in 1915, and I plays guitar, my father played guitar and violin, and my mother played harmonica, and my name is Honeyboy Edwards, and that's about whatever.

This is me.

Charley Patton-- he was a Indian.

He dressed clean, wore his hair out curled to the side.

He was a Indian.

Yeah. He had some good-looking womens.

I used to go with one of his womens.

Well, he was attracted at the time because he made chords that didn't too many people make, but Charley Patton, they called him the founder of the Delta.

He was a good blues player back in that time, and his--his name was ringing all through the Delta-- Charley Patton, Charley Patton.

He played for all the country dances.

Patton: ♪ I'm gonna move ♪ To Alabama ♪ I'm gonna move to Alabama ♪ I'm gonna move to Alabama... ♪ Redford: The 96-year-old guitarist Homesick James had vivid memories of Patton's performances.

He--he was... McMahon: How did he manage to be heard with just guitar and voice?

Well, Charley-- he dranked a lot of whiskey, a lot of white whiskey, and he'd break up his own dances.

He broke his own-- he'd fight.

He'd get to playing the guitar, and somebody'd say, 'You want to fight?'

He'd break up his own dances.

Charley died in '34.

He had got to fighting at Holly Ridge, and then some guy had cut him here on the throat.

Redford: Two years after Patton's death, Robert Johnson blended his style with the latest sounds from Chicago and St. Louis and made the most famous Delta blues recordings of all time.

He, too, was discovered by H.C. Speir and is now considered a forefather of rock 'n' roll.

His most direct musical descendant was his stepson, 91-year-old Robert Lockwood Jr.

[Playing 'Love in Vain'] ♪ When the train left the station ♪ ♪ With two lights on behind ♪ ♪ When the train's pulling away from the station ♪ ♪ With two lights on behind ♪ ♪ The blue light was my blues ♪ ♪ And the red one was my mind ♪ All my love's in vain Oh, that was one of Robert Johnson's tunes, and the name of it is 'Love in Vain.' Yeah.

MacMahon: When did you learn that song?

Oh, Jesus ... I learned that song a long, long time ago.

Oh, when I was-- I learned that song when I was, uh, about, uh... about 16.

Who taught it to you?

Robert Johnson.

I was on his case.

Everything that I learned from him at that time, he showed me about twice.

I'm known as somebody that can play his material.

Darned near everybody else messes it up.

Edwards: See, blues supposed to be made to play slow like Charley Patton, but a lot of the boys that's playing the blues now, some of them playing the blues fast, and, uh, it sound all right, and they be jerking and going on, you know, and not hitting on nothing, you know what I mean, but they think they are.

Blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

Just a few can sing.

They sound, 'Ohh.'

They can't sing, but they can play.

Yeah.

I'm not a doctor, but what I think their voice cords is not like ours, know what I mean?

Their voice cords is not like ours.

That mean they can't control it.

They can play, but they can't-- just a very can.

Now you catch some white bro can sing good, but just a few of them now.

Just a few.

Haw, boy!

[All three laughing] Kenny: Charley Patton was able to share his experience in his music, and--and what it represented was one person on a platform representing a whole environment of African Americans being underprivileged, African Americans being disenfranchised, African Americans not having an opportunity, an equal opportunity in this country.

Tracy: So I think the translation from blues all the way to rock, now to hip-hop, was just a metamorphosis and a, um, culmination of the entire African-American experience that was rooted in slavery, and we've always found a way to scream through the music.

♪ I thought, baby ♪ That you would never dog me round ♪ ♪ Oh, I can tell you, honey ♪ Oh, you gonna think about poor me someday ♪ ♪ I said, then you gonna be sorry ♪ ♪ Oh, that you treated poor me this a-way ♪ Redford: In the years following Charley Patton's death, the Mississippi Delta was transformed.

Lester: Mechanized machinery came in, and so instead of using mules and people, they just used tractors, and one man on a tractor could do what a hundred men with a mule could do, and it changed the whole labor workforce completely, and the people all left.

Redford: Sharecroppers, mule drivers, and cotton pickers streamed up Highway 61 on the great migration north to industrial cities like Chicago and Detroit.

They took only a few possessions, their stories, and their music.

Taj Mahal: It's really hard to know how far-reaching the influence of Charley Patton is.

I mean, he influenced the first generation of Delta guys, you know, and those guys are, like, Muddy Waters, B.B. King, and John Lee Hooker and the younger Delta guys like Robert Lockwood, but his big thumbprint is on Howlin' Wolf.

Wolf clearly states that he went over to Patton and sat down, and Patton showed him his tunes and the way he played them.

You can't get that unless you're right next to him.

You had to be able to watch him play it every night for several every nights.

♪ If you see me running ♪ I'll come streaking by ♪ You better run, boy Oh, yeah.

♪ If you see me running ♪ I'll come streaking by ♪ She got a bad old man ♪ I'm too young to die Taj Mahal: When you hear a lot of the early Wolf stuff, you hear Patton in there, but Wolf brought it to a new generation and then carried it forward.

Announcer: Next time on 'American Epic,' the record industry extends its reach, showcasing the country's diversity... Man: Everyone was so excited to have a Cajun song on a record.

Taj Mahal: The Hawaiian music was really kind of the rage.

Announcer: a lost pioneer is rediscovered... Woman: People just knew him as Mississippi John Hurt.

Announcer: and a musical melting pot transforms American music forever... Different man: A lot of these songs have changed the world.

Announcer: in 'American Epic.'

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪