A new study of oxygen isotope ratios and heavy metals in the tooth enamel of Neanderthals who lived and died 250,000 years ago in southeast France suggests that they endured colder winters and more pronounced differences between seasons than the region’s modern residents. The two Neanderthals in the study also experienced lead exposure during their early years, making them the earliest known instances of this exposure.

Enduring harsh winters

Tooth enamel forms in thin layers, and those layers record the chemical traces of a person’s early life—from climate to nutrition to chemical exposures—a little like tree rings on a much smaller scale. Archaeologist Tanya Smith of Griffith University and her colleagues examined microscopic samples of tooth enamel from two Neanderthal children from the Payre site in southeastern France. The teeth were dated to around 250,000 years ago based on thermoluminescence testing on nearby burned flint, and the set of samples recorded about three years of life.

One important clue to past environments is oxygen, which comes from the water a person drank or the plants they ate. The ratio of the oxygen-18 isotope to oxygen-16 depends on temperature, precipitation, and evaporation. Generally, higher ratios of oxygen-18 indicate warmer, drier conditions with more evaporation.

In the Payre Neanderthals, oxygen-18 ratios increased in the summer and dropped in the winter in predictable seasonal cycles, which Smith and her colleagues could compare from one week to the next. The data suggests harsher winters and more pronounced seasonal changes than today, and information about seasonal shifts can be combined with other details recorded in tooth and bone to explore how climate affected Neanderthals’ development and life histories. Climate is often credited with driving hominin evolution, but it’s rare that archaeologists can directly link the two.

“This is particularly germane for Neanderthals, who survived extreme Eurasian environmental variation and glaciations, mysteriously going extinct during a cool interglacial stage,” wrote Smith and her colleagues.

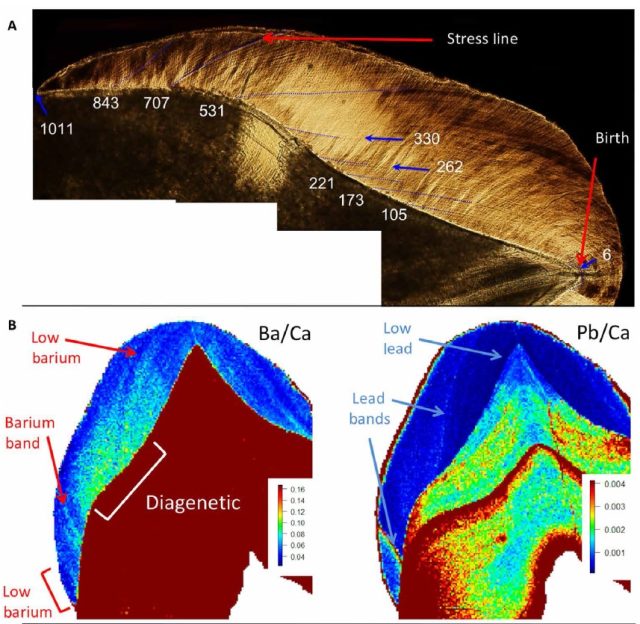

The cold seasons were hard on Neanderthal children, because both of the ones from Payre bear lasting traces of illness or malnutrition during their early years. That kind of physiological strain impacts how the body absorbs and processes minerals, including the ones in tooth enamel, and that can leave a visible line across the tooth, marking the layers of enamel added during tough times. On a lower-left first molar from one child, Payre 6, the layers of enamel laid down during the late winter or early spring, not long before the child's second birthday, show a line marking about a week of sickness or starvation. And another child, Payre 336, apparently suffered a similar two-week episode in the winter and another week the next fall.

Other studies have noticed that Neanderthal teeth often bear the lines left by these periods of hardship; according to Smith and her colleagues, many of those episodes probably happened during the cold, difficult months of later winter and early spring.

Oldest evidence of lead exposure

Heavy metals in the bloodstream eventually settle in bones and teeth, and Payre 6's tooth enamel contained noticeable amounts of lead from the time the child was about 2.5 months old. Around nine months of age, in the depths of winter, a band marks a sudden spike in lead exposure—about 10 times as high as the lead levels recorded in the rest of the tooth. A little over a year later (about two months after the bout of sickness already mentioned), another band of concentrated lead marks a sudden increase in exposure in late winter or early spring.

Payre 336 also seems to have been exposed to high levels of lead, once in the spring and again in the winter or late fall.

That’s the oldest physical evidence of lead exposure archaeologists have uncovered so far, and it’s probably a consequence of sheltering in caves close to underground lead deposits. At least two lead mines lie within 25km (15.5 miles) of the Payre site, well within Neanderthals’ likely foraging range. The early, constant lead exposure may have come from contaminated water or juice; Smith and her colleagues say milk probably isn’t to blame because that would also have deposited extra barium in the enamel.

At around nine months, Payre 6 may have started getting more lead from the solid foods they were starting to eat. The lead exposure isn't linked to the episodes of sickness or malnutrition, and it's impossible to know how it might have impacted these two children's health, but Smith and her colleagues note, "Decades of research have shown there is no safe level for lead in humans and other animals."

A hint about demographics

Lead isn't the only heavy metal that finds its way into teeth. Nursing often leaves higher levels of barium in a child's tooth enamel. In Payre 6, enamel laid down during the first nine months of life contains high levels of barium, but then it begins to taper off—lasting evidence of the moment a Neanderthal mother began weaning her child off milk and onto solid food. But that process lasted until the child was around 2.5 years old, when the barium signature in their tooth enamel finally fades out altogether.

That's about how long nursing lasts in some modern human societies, especially hunter-gatherer cultures whose lifestyles may resemble those of Payre 6 and his family.

That may eventually help fill in another piece in the puzzle of Neanderthal extinction. Populations that nurse their children longer also tend to have lower birthrates, which means those populations often don't grow as quickly as those that wean their children sooner. For Neanderthals, trying to compete for territory against newly arrived Homo sapiens, population growth may have played a role, though it's too early to say for sure.

Payre 336's tooth enamel didn't show any clear patterns of barium levels. The only other evidence of Neanderthal weaning is a 100,000-year-old tooth from Belgium, but instead of the gradual changes of weaning, its barium levels drop off abruptly around 1.2 years of age, as if the child had been suddenly separated from their mother. Smith and her colleagues say archaeologists need more evidence in order to draw conclusions about when most Neanderthals weaned their children and how that compared to their Homo sapiens neighbors.

Science Advances, 2018. DOI: 10.1126/science.eaau9483 (About DOIs).

A earlier version of this article stated that the Neanderthal teeth were radiocarbon dated; a more recent human tooth from the same site was radiocarbon dated, but the Neanderthal specimens were dated based on thermoluminescence of nearby burned flint.

reader comments

39