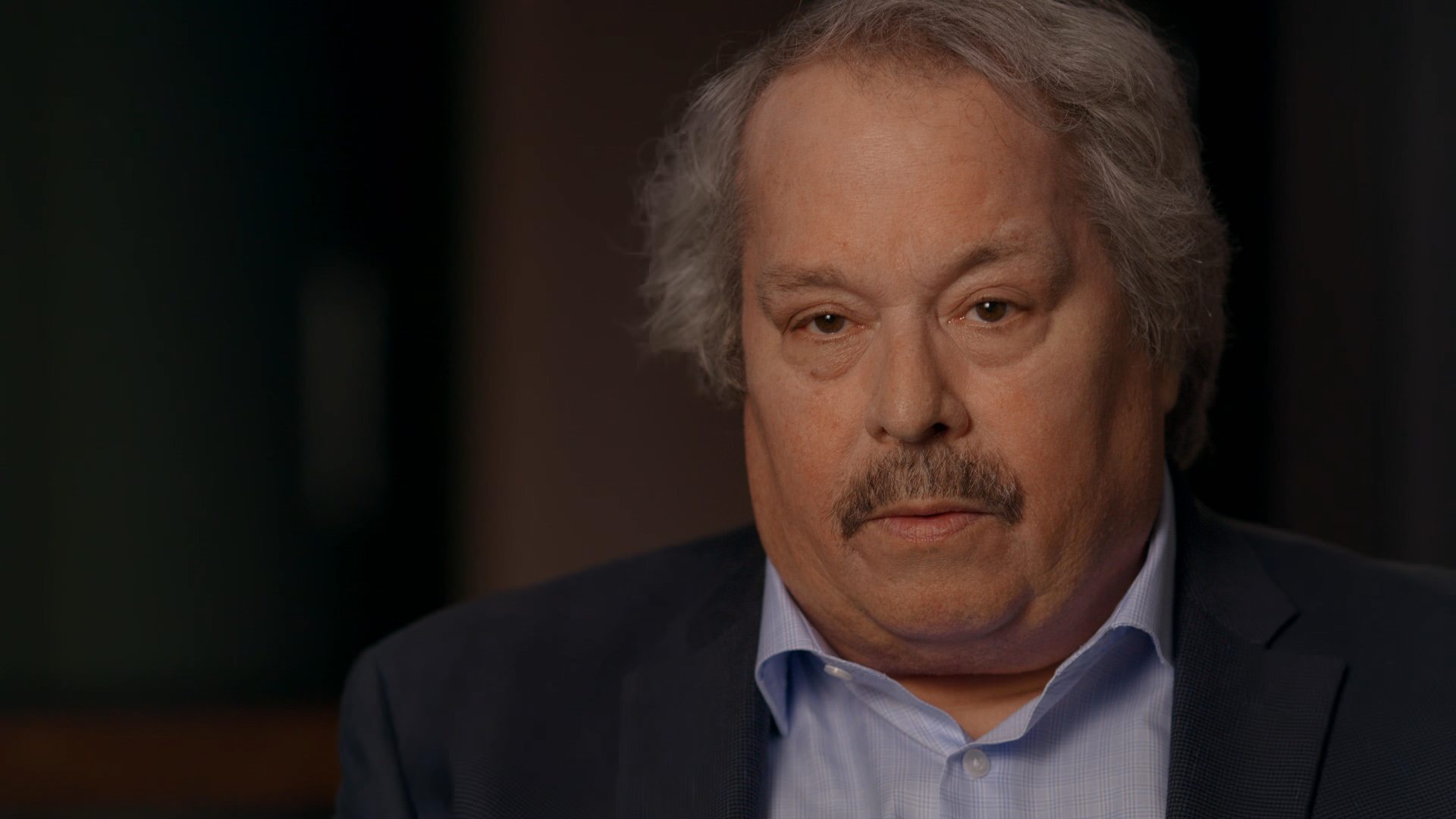

The FRONTLINE Interview: Sandy McIntosh

Sandy McIntosh got to know Donald Trump more than half a century ago, when the two were schoolmates at the New York Military Academy. “We would meet occasionally,” McIntosh says. “He would always ask how I was doing. Sometimes he’d give me good advice. I think throughout the whole time that we knew each other at military school, he was kind to me and attentive when I needed it, got me out of some jams.”

Today, McIntosh is an author and publisher of Marsh Hawk Press. In the below interview, he discusses what Trump was like as a teenager, young Donald’s early efforts toward “making his brand,” and a formative relationship between Trump and a mentor at the academy, Col. Theodore Dobias.

This is the transcript of a conversation with FRONTLINE’s Jim Gilmore held on July 14, 2016. It has been edited for clarity and length

So you met Donald when you were nine or 10 years old. Your families knew each other.

About 10 or 11, right.

Talk a little bit about how your families knew each other, your first memories of Donald Trump.

Our families were both members of the same beach club at Atlantic Beach on Long Island. Even though we were in the same court of cabanas, I don’t think I’d ever met him until my father and his father introduced me to him. His father I’d seen around. He used to wear, at the beach, a tie, jacket and a hat all the time. And every time he passed the ladies, he would tip his hat to the ladies.

The reason for the meeting was because my father — I think he had some business relationship with Fred Trump; I don’t know exactly. But in any case, Donald had been going to New York Military Academy for a year or two years, and my father decided that after I’d gone to progressive school for seven years and had learned to bake bread and dip candles and speak a little French and German and knit … he thought I needed to be fixed.

So the military school was his idea. Fred Trump asked Donald, or told Donald, to take care of me. So we spent the summer at the beach club. Donald had set up a big tent on the beach, and he and his younger brother, Robert, and older sister, who I don’t remember, we played cards, and Donald taught me how to play canasta. He told me about New York Military Academy and all of the things that were going on there, and he seemed to really be enjoying it, and it just scared the hell out of me, and I was plotting already how to escape before I even went up there.

But I think his father said: “Look, just take care of this kid. Show him the ropes, and keep him out of trouble.” I went up there, and during that first year — and Donald, I did see him. He was up in the, I think, the middle school or already in the upper school. I was in the lower school building. But we would meet occasionally. He would always ask how I was doing. Sometimes he’d give me good advice. I think throughout the whole time that we knew each other at military school, he was kind to me and attentive when I needed it, got me out of some jams. …

What was Donald like?

Well, he was a tall, lanky kid, blond hair. I didn’t know him. I mean, there were some kids like me who had a gang on the beach, and we had fights with another gang at some points. He wasn’t part of that at all, or at least I didn’t know him to be part of that. I think when his father told him to take care of me, he took it seriously, and he did. He just followed that order and did it.

So my relationship with him at the beach club was cordial. I wanted to be more friendly with him. He wasn’t standoffish at all, but he was just kind of doing a job. He was being friendly to me because he was told to, or he felt he had to be.

He was a little older than you?

Two years older than me.

Who did he hang out with?

I don’t know. I don’t remember him hanging out with anyone in particular. I don’t remember him having very close friends. I think at military school, that was the same thing, that he was respected by a lot of people. He became a very good athlete, for instance, and people respected him, but I didn’t know anyone who would say, “Well, this is my best friend,” or who he would share intimacies with as friends do.

Why do you think that is? I mean, there is a story out there that he was very competitive, and the competitiveness prevented him from having close friends.

Well, some people have said that; for instance, George White, who was the first captain the year that Donald graduated, because he lived with him in the senior staff quarters, said that there was some arrogance or some sense of being elite and that Donald looked down at them and so forth. I never experienced that, but I did think that there was a lack of empathy there, and not just because he was so competitive in sports, but I think this is just part of his personality. I mean, he never laughed at any of my jokes, and to me, that’s an important part of friendship.

Well, are you funny, though? I guess that’s the question.

Well, that’s another question. I think I am.

What was his dad’s reputation at that point?

His father’s reputation?

Fred, yeah.

I was a kid, and I didn’t know much about what was going on. I knew he was involved in building, and Donald would say that. I think I remember him telling me that he’d go onto job sites with his father and look around. But I sense, putting it sort of backward from looking at Donald as he was in military school, Donald was very precise about his dress. Everything was always polished and so on, and he was a very handsome officer, very handsome cadet.

But I think that probably this paying really close attention to things came from his father. His father, I understand, not only supervised jobs, building jobs and so on, but also knew every component of the different craftsmen’s work and was able to say, “No, you want to do it this way,” and he’d be right.

So I think Donald learned that. Donald is, you know, he’s a hands-on person. He’s very particular about things. I met one time in Florida a carpet cleaner who had cleaned the carpet in Mar-a-Lago, and he said that Donald was just around him all the time just saying: “Look, this is not right. You’ve got to do this again.”

What was his relationship with his dad?

Well, it’s almost as if he just took orders from his father. I don’t know. They may have had a very good relationship between them; I don’t know about that. I think that somehow, Donald was very angry. I never saw his anger, but I know he told me about trouble he got into at his elementary school, I think throwing an eraser at a teacher or something or other like that. That tells me that there’s anger in there. All the time I knew him, I think he was very contained.

I only heard of one time when he was in a fight. He had a roommate who — it was very important how we made our beds. They had to be perfect — the top 10 inches up there, the fold six inches, 45-degree angle — and had to be taught. I don’t know if anybody ever threw quarters on them until they bounced, but that’s the thing that had to be. For some reason, Donald messed up his bed, so he grabbed a broomstick and went after Donald and just hit him with it. Donald jumped on him and he said that it took three guys to get Donald off him. But that’s the only incident of fighting that, aside from sports, that I ever saw him or ever heard about.

Tell me the story again. Donald took offense to the way the guy made the bed or what?

… Donald somehow messed it up. I don’t know what the reason was for it, but it angered Ted Levine so much that he grabbed a broomstick and hit Donald with it. And then Donald fought back and actually got him down to the ground and was beating on him until three guys came to haul him off.

But that seems like a kind of typical thing. There’s nothing exceptional about that. We were in a culture of hazing at the military school. Everyone, I mean, that’s just the way it was. The handbook, or the regulation book, even talked about hazing, certain things that would go on. And hazing, when you followed it and you got through it, it would be your entrance into an elite society. This was a tradition of military academies. Definitely as far back as anyone knew, this was a component.

… How different was it, and how different was the real society from the way you guys were being taught?

I think we learned in military school, we learned a certain way of behaving which had a lot to do with ordering each other around or following orders. But when we graduated, we went into a different society, a civilian society. Either we went to work or we went to college, and in either case, we had to learn how to live as civilians. And that meant that you can’t just give people orders. They won’t follow them. …

How do you think that affected Donald Trump?

When I talk with friends of mine who graduated at the same time, I think that all of us started in business at either the lowest rung or the second lowest rung or so on, and we had to learn these things. We had to learn how to live socially like that. Donald may not have had that experience because he had a lot of money. His family had a great amount of money, and he started at the top. He didn’t start in the ditch; he started behind a desk. So perhaps he didn’t have to go through that maturing process that we did.

Leaving him with the thoughts, possibly, that what he learned at the military school and the realities of being able to order people around was indeed the way it should be?

Yeah, I think so. When I listen to Donald now speaking and read reports of what he said, the circumstances are of course 2016, but the time — the conversation, the way he’s talking, the topics he talks about, seem to be 1964, because in our barracks, we talked the same way, probably a lot more profanely, about minorities, about people of different religions, about women. In fact, our biggest advice in our lives came from Playboy magazine. That’s how we learned — That’s what we learned about women, so that was all of my adolescence. And that’s why getting out of military school was difficult. You had to realize that you couldn’t just follow the Playboy philosophy.

But I think that the things that we talked about at that time in 1964 really are very close to kind of the way he talks now, about women and minorities and people of different religions.

Why do you think he got stuck there?

Well, I think that people change only when they’re pushed, and I don’t think he was pushed. I think that he started out at the top and simply continued the way he was going. I mean, I hope I’m not being unfair about this, but when I hear him speak, I hear these echoes of the barracks life that we had and that we grew out of.

Why was he in a military school?

Well, I think because of his behavior in elementary school. By his own admission, he assaulted a teacher, and he said that he just loved to fight, any kind of fight — physical fight, yelling and screaming, that kind of thing. That tells me that there’s a lot of anger inside him. But when I knew him in military school, I think he may have been reckless before military school, but I think once he got into it, I think he channeled all of that. When he was first there, he was in F Company, which was run by Theodore Dobias, who was the major, who had himself been a graduate of the school and had come back and ended up, in fact, teaching there for 50 years and passed away only recently at age 90.

But Donald said that Dobias was his mentor. In the beginning, Donald was rebellious when he first came into the school, according to Dobias. Dobias really, according to Donald, slapped him around whenever he needed to. I know there was a lot of violence that went on, because the next year after Donald had been in F Company with Major Dobias, I went in, and I experienced a lot of the same things.

… I think what Donald did was after Donald went through the hazing, the new-guy hazing at military school, he started learning from Dobias. He started watching Dobias and started getting his modus operandi. He played in all the sports that Dobias coached, followed his guidance in that and became a very good athlete. Watching him play baseball, played football, he was very good. He never gave up at all. And Dobias just loved him for it, and the rumor was that Dobias would do anything for him.

When I was there in Wright Hall, my grades were never terrific except in English, I think, but Latin was the worst. Dobias hauled me onto the carpet about my Latin grades and said, “Well, I’m going to teach you about how to get better grades.” He said that, “You’re going to join the boxing group.” The boxing group was an informal thing he put together in the lobby of the building, and he’d have little — it seemed like he was always pairing little kids against big kids, and the little kids he’d be training to box, and he’d put them against the big kids. There was some humiliation in that. Perhaps it was good training, I don’t know, but it was not anything we could do voluntarily.

Before I was in military school, my father had been very enthusiastic about judo, so I’d learned judo, and we actually did exhibitions in different places, and I was able to do it. So when I was put into the ring, Dobias said: “Don’t use judo. You’re not allowed to use judo.” And this kid started after me, and he was punching like a mosquito, little hornet. I didn’t know what to do. I wasn’t a boxer; I’d never had training on that. So I simply went over and picked him up by his belt and threw him down on the ground. And the kids who were watching were a little upset, because they knew Dobias had given me a direct order not to do this.

So Dobias put on the gloves, and he got in the ring and said: “I’m going to teach you how to do it. I’m going to teach you how to take it and how to give it.” And he got in there, and he punched me around, not hard, but more like the humiliating kind of taps and so on.

This went on for several days, I think. I can’t remember how long — to me, it seems like it went on for years, but I know it didn’t. But one day I met Donald as I was walking across the campus, and he asked me how I was doing. I told him what had been going on, and he said, “Well, you’d like this to stop, right?” And I said, “Yes, I would very much like this to stop.” And he said, “Well, I’ll have a word with Dobias.” Then several days later, the boxing stopped, and I was actually transferred from that building to the upper school main barracks.

Now, whether Donald had a hand in that or not, I don’t know. I can’t be sure. But I’d like to think he did.

So he was, in fact, still looking after you, really?

Yeah, and that went on to the last day that I knew him, which was in 1964, right before he graduated.

Go ahead.

No, I was just going to say the conversation — we were on the baseball field, and we were talking about one of his games in which he had hit a home run or something. He said, “You remember how I hit that ball?” And I said, “Yeah, I think it went right over the left fielder’s head.” And he said, “No.” He said, “I hit the ball out of the park.” Said: “Remember that. I hit the ball out of the park.” Well, I thought this had been a regular conversation between kids, and I thought that seemed kind of strange.

Maybe it’s not fair to do this, but I look at Donald now and I think, well, he’s making his brand; that’s one element of his brand that he wants to share.

Exaggeration.

Perhaps, a small amount. Rather than just winning the game, he had to knock it out of the ballpark.

Not a man of subtlety?

No.

And you saw that in other ways with him?

Well, all I can say is things — for instance, in his senior year, he’d have his parents, who came up to visit him on the weekend, bring one girl or another. They were always beautiful girls. Every week it seemed like he had a different one coming up. I don’t know whether he actually knew them or not, but it seemed like he was, again, making his brand, doing this — and it was such to an extent that he was elected as the ladies’ man of his class. Now, I don’t think there was a ladies’ man in the previous class, so I think he just took this honor out of that. That was another point in his brand.

So when you say making his brand, what do you mean? He becomes famous eventually for creating the Trump name as the sign of excellence, and that’s what he sells. To some extent he moved away from the business of building to the business of selling his name.

Exactly, yeah.

Explain how you saw that even in his younger days, how he was creating this myth.

I can’t say how I saw it except for those incidents. I mean, I have a theory about it. My theory is that because — I have no knowledge that he had intimate relationships or really deep friendship relationships with people, so he wasn’t prone to empathy, but he was prone to strategy. I think that at some point, he began to work on that. I didn’t see it before his senior year, but my contacts with him were sporadic. We’d pass each other on the campus. …

Just to follow up on the Dobias thing, you say that in some ways he took on some of what Dobias represented; he saw it as a successful way.

Right.

What did he take from Dobias? I mean, was it a sort of bullying style, or was it a — what did he learn? What did he take on from Dobias?

I don’t think he took anything of Dobias’ personality. … What he got — in F Company, in Wright Hall, in the lobby, Dobias had put up signs that have golden sayings and so on, all over the walls, and very nicely done, expertly lettered, hand-lettered and so on. But there was something about them that struck me right away, because the signs were, if they were on the same subject, they seemed to be contradictory.

For instance, one of the signs says, “When the great scorer comes to write against your name, he writes not whether you’ve won or lost but how you played the game.” And the sign next to it says: “Winning isn’t everything. It’s the only thing.” So you have these two signs that seem to be canceling each other out. There were plenty of other instances of that. At one point, when I thought I could not get hit or something, I asked Dobias, “How come the signs were like this?” And he looked at me as if I were an idiot and said, “Well, look, you look at them, you read them, and you take the one that is important to you then.” And in Donald Trump now, as a candidate, I hear the same kinds of double statements about things. In one case, several months ago when Ben Carson had just left the primary, and he said, “Well, there are two Donald Trumps,” and Donald Trump, who was standing next to him, said, “Yes, there are two Donald Trumps,” and then he said, “No, there are not two Donald Trumps.”

When Donald addressed evangelicals, he said that he was going to try very hard to get judges who would reverse the marriage equality laws, but when he talks to the gay community he said, “I will protect you; I will lead you.” So he has both, and I think this is throughout his whole campaign, is that he’s able to put one foot in this opinion and one foot in this opinion and come out on top somehow. And people who like him are not bothered, apparently, by the contradictions.

Why does he use the contradictions, though? I don’t understand.

Well, I think when you use contradictory statements, as Dobias said, you pick the one that you need at the moment. If you said, “Well, didn’t you tell me that winning is the only thing?,” and then if you didn’t want that statement, you’d say, “No, no, it’s when the great scorer comes to write against your name, it’s how you played the game, right?” You can have one or the other of those things. I think Dobias thought of that as a terrific debating technique, and I think Donald does, too.

So whatever works at the time, basically?

Right.

… One of the primary things, it seems, about Donald Trump is he’s a winner, not a loser. He’s a winner, always win, always succeed. From what you know of the guy, this winning/losing thing about him, where does that come from?

Where it comes from I don’t know. … But I do think that Donald had a way, or has a way, of approaching reality, let’s say, that is — well, I’ll give you the one example I think I have of this, is that during second mess lunch — I think it was second mess, or first mess — the officer of the day or someone else on the staff would get up and read the orders of the day, give the prayer, and order everyone to sit down. And that was done — this was at my time 400 cadets in a big hall, and all standing in front of their tables.

There was no microphone. In order to be heard, you had to read everything by going left to right, right to left. You’d say, “Attention to order, detail for tomorrow,” and then you’d list all this stuff. Then you’d read the rest of the orders, and you’d give the prayer, which went, “Oh Lord, we thank thee for the food we’re about to receive, amen.” And then you yell, “Seats,” and everyone sits down.

For some reason, when I was a sophomore or something, I was chosen to do it one day. I don’t know why exactly, but I got to sit at the senior staff table with Donald. Before I did this, while we were standing around waiting for everybody else to come in, I said: “Look, I don’t know how to do this. What happens if I screw up? What happens if kids laugh at me?” And he said, “Look, it’s really simple.” He said: “You just visualize everyone listening to you intently and keep that picture in mind. Keep that picture in mind of you winning. You’re the winner out there. Go out there, and don’t give those orders until they’re listening to you.”

So I went out there, and I tried it, and I yelled “Seats,” and everyone sat down. It was like sacks of flour falling from the ceiling. So I went and said to Donald, “You know, well, they all sat down; it worked really well.” He said, “Yeah, well, they sat down because they’re all starving, but,” he said, “you did OK.”

But this idea of visualizing yourself as great, I think this comes from the involvement that Donald and his father had with the Marble Collegiate Church with Reverend Norman Vincent Peale. …

What did Norman Vincent Peale say? It was basically, the bottom line was that success will come to you if — success is godly; financial success shows that God is —

I know what it is: The Power of Positive Thinking. That’s it. I think that now in looking back on it, which may not be fair, but from all these years — and I understand that Donald was involved in the Marble Collegiate Church and with the Reverend Peale, and that he did visualize these things, and he was giving me a little insight into doing this.

I think that if in fact Donald — the idea behind this is that you see yourself as the winner and you hold that image up to yourself, almost like looking in a mirror, but you’re the winner in the mirror, and the positive side of it is you can keep winning as long as people don’t stop you from doing it. I mean, if you’ve lost the battle and the soldiers are all dead on the ground and you’re still holding up and say, “We won, we won,” I mean, you won until the audience walks away.

But I think the negative part of that in living is that if you hold an image of yourself up and you’re just staring at yourself as the winner, there’s a lot of collateral damage. You lose people who are close to you, lose out on it, because you’re aiming for one particular winning point.

What do you mean, people around you lose out? How so?

No, I think that it really becomes a very self-centered occupation of just staring at yourself as the winner, and you’re not really open to discussions of other people’s opinions and so on. You go by your own gut reactions because you’re looking at the picture of the winner. Anyway, this is my theory here.

… And the adults around him? Did he seem to migrate towards the adults to some extent? How did the other teachers, the adults, treat him?

I don’t have any memories of that.

Okay.

Do I? Well, his coaches were very friendly with him and as they were friendly with any good athlete, you know. … But I don’t think there was any special relationships except perhaps with Dobias. I mean, he said Dobias was his mentor, so I assume that there was a special relationship.

What do you think that he got from Dobias that he didn’t get from his dad?

Dobias was a passionate man. I don’t have any recollection of his father being passionate at all. I see his father at the beach even, with a suit and a tie and a hat; a clipped very kind of military mustache. And simply being correct. I didn’t spend any time with him other than little bits of time at the beach club and the military school.

But cold?

Yes, cold … he was not a warm person.

… I’m just going to talk about your overview of things after the school. But are there any other stories about the school that you remember that you think are important to understand Donald Trump or what he was like as a kid?

I don’t think I have a particular story, except to say that while he never — I never knew him to be involved in any hazing incident. … But I think that even if he didn’t participate in the hazing, all of us were part of this culture of you beat on kids when they didn’t do the right thing. I mean, I have bad memories of myself mistreating maybe not physically, but mistreating a young kid or young kids when they were new and coming in and just making them feel terrible and just venting my anger on them. There’s a kind of a whole fugue-like psychological movement going on in there which shouldn’t be found outside of military school.

It’s a bullying technique that I guess can be seen in the way — like when he’s debating other candidates and calling them names and belittling them, using belittling tactics as one of his main ways to drive his point across. What in him as a candidate do you see that possibly are tactics that he learned from military school?

Oh, I mean these are not tactics he learned from any adult officer, I don’t think — maybe Dobias a little bit, but I think these were things that went on in the barracks. Friends of mine discussing Donald, as he is now, are not really surprised by anything he says — maybe more surprised by some of the quick twists and turns that he does and maybe appalled by his attitudes that we hadn’t thought about in all the years since we actually were like that. You know, we’re 16- or 14-year-olds and talking about different races and about women and what we’d do to them and all this stuff. Then here you have a grownup person, and it’s the same voice; it’s the same material.

… So when you were watching him in the debates, and he would denigrate “little Marco” or whatever, or “low-energy Jeb,” what were you hearing? What were you thinking as you watched the debates?

Just the usual kind of 14-year-old’s arguments against others, berating other people, just that. It didn’t go beyond that. I have to say that he has a talent for picking out nicknames for people, right, that are denigrating and — well, he’s very concerned with size, as we know. It’s either big or small, right? He has big hands, and I did write a piece in which I said I showered with Donald Trump, and when — after he made that statement, people who I knew said: “Well, you went to military school with him. Was that true?” And I have to say that I don’t know, because I must have showered with him a hundred times, but you didn’t look at that. You didn’t stare at other kids because it was dangerous to. You couldn’t do that. And because there was just no time. Showers were three, five minutes, that’s it; you’re out; you’re on to the next thing.

That was a question I was not going to ask you. (Laughs.)

Oh, OK.

Was it a surprise to you when he went into his dad’s business?

No. I really didn’t think much about him after — his name cropped up in the newspaper or sometimes on TV or something — in all the years. It’s really been four and a half, five decades since we were in military school together. So I did know about him during that time. One time, we both had a book out at the same time. He had The Art of the Deal, and I had a book called Firing Back. Both books were featured in the New York Military Academy alumni magazine, but that’s the only connection that we had.

… When The Apprentice came on in 2004, was that the Donald Trump on The Apprentice that you knew?

No, it wasn’t. No, I mean, the Donald Trump who — and I didn’t watch The Apprentice except once maybe [in] passing onto a cooking show. To me, I saw him as a considerate, fairly soft-spoken person when he was with me. I have to say that I think he followed that promise that he made to his father. Even [though] I wasn’t such a little kid when he was graduating, but still he followed that promise to sort of take care of me like that, or make sure that I was OK.

I think that part of him is not visible too much as a politician or in anything I know about his life right now. And it’s too bad. I miss that, you know? …

The fact of The Apprentice and being on television for however many — over a decade, that he was on television is seen as the top CEO in America and telling everybody, “You’re fired.” How do you think that helped launch him, helped sell his brand?

I think that people who were looking for clear answers, for decisive answers, to very complex issues that we have, I think that’s very attractive. Someone who will get up there and say to all those people who are bothering you, “You’re fired,” or to the government who seem to be stealing your money or just impinging on your freedom, say, “You’re fired,” and they go and they leave — he’s a kind of superhero in a certain sense.

In fact, I remember he characterized himself as a kind of superhero at some point. I think that’s a very attractive thing for some people.

… Reality television seems to have more weight these days than what the nightly news does.

That’s probably why he’s successful in this, because he’s just come out — I mean, The Apprentice was one thing, but I’ve seen his wrestling, the tapes where he attacks McMahon, right, Vince McMahon, just jumps on him. Now, he’s wearing the same suit and the same tie that he wears in the debate, but now he’s jumping on the guy physically and pulling him down. And then he shaved his head. You’ve seen this, right?

I haven’t yet.

Never? You’ve got to see it, right. No, Vince McMahon is held down. He looks like someone who’s about to be electrocuted, and Trump has his shears, and he just shaves his head. I mean, there’s The Apprentice and now the candidate, and I don’t see any disconnection between them. But I do see this is not the Donald that I knew, and I do see this as a kind of culmination of building a particular persona, building a brand.

He’s a genius, really, when it comes to that, at PR, at building the brand, at using the media?

Yeah. He says he has fun with all of it. I don’t know how much fun he’s having nowadays, but I can see having fun like that, calling up a reporter and pretending to be his own publicist and then saying how great Trump is. That’s fun, you know, if that’s your kind of fun.

So last June he announces. Did you watch the announcement?

Yes, I did.

… And that day, announcing for president of the United States, are you surprised? Are you amazed?

Of what he said or that he was announcing for president of the United States?

Just that it’s happening, a guy that you knew? What’s your impression?

… I was revolted by it. And the idea of putting up a wall along the American border is — what’s going on with that? There’s always thinking, well, something else is going on beneath it. But there’s no connection between the Donald I knew and this Donald, even though there is. I mean, I know there is one; I just don’t know what it is.

… You knew him as a kid. He was a good guy to you. You saw both sides of him. You saw him learning his persona, learning the trade of selling the name, earning and selling the brand. You saw both sides of him. So you look at it now, and the fact that he might be possibly — very good possibility. The polls today show that he’s got a better possibility than Hillary right now.

Right now, yeah.

What’s your thoughts about what kind of presidency that he would have?

No matter what you think about Hillary, at least she understands how government works. She has a lot of experience with it. Donald, I don’t think, has that understanding of how government works. This is going to be all new for him. Depending on the vice president he picks, he is going to let the vice president, who may have more experience in government than he does, have a free hand? Well, I don’t think so. Donald does everything by gut, and he really relies on himself as his own adviser. So I think that there’s trouble ahead, and a lot of adjustment. On the other hand, he can take things and turn them around. He has that ability. He may be able to turn this around. If he’s elected president and he wants to stay as president, he may be able to work something out that will work; I don’t know.

Become a different Donald?

Become a different Donald, right. Can he do that? I don’t know.

Did he have that in him as a kid? Would he listen to people? Did he seem to be convincible?

No, I don’t think so. I mean, he was, as I say, very pleasant all the time to me, but I don’t know if he listened to anything I said back to him. I mean, we talked a lot, but now as I remember it, it was more of a Donald monologue. He was telling me all about the military school, all about his playing baseball, his playing football, all about this and about what a great thing he was doing, what a spectacle he was creating. But I’m sure I had something to say, because I usually have something to say. But whether he responded to it or not, ever, I don’t know.

He’s not a good listener.

I don’t think so. I mean, he did listen to me a couple of times when I needed it, but I wouldn’t say there was empathy in it, no.

How important is empathy for a leader?

Well, I think it’s vastly important. If it’s a choice between feeling what another person is feeling and understanding it and try[ing] to reason and come to a decision that way, that’s one way of doing it. Telling people that you’re fired and that’s your way of making a decision — I’d go for empathy.

And he doesn’t have that?

I don’t really feel that he has empathy particularly. He’s not a terribly empathetic person.

And the problem with that is?

That it limits you in what you can do. I think that he recognizes that, whether he could name that or not, but I think he recognizes it, and he spent his life strategizing. There’s empathy in which you sort of are moved by the way other people in the world are acting and what they’re feeling and so on, and you move that way. Or strategizing, which doesn’t require any people, really — you just make a strategy and you follow it. If you’re a good strategizer, it’s going to work. And if you’re not, or if you’re just a mediocre strategizer, it might work, might not work, I don’t know. Up to this point, what he’s wanted to do has worked. The question is, is it applicable as president of the United States?