We are obsessed with staying dry. We build shelters, carry umbrellas, even devise new materials that shed water. There’s good reason for it, too—an excess of water can cause everything from hypothermia in people to icing on airplane wings.

That last was of particular interest a team of engineers, who were curious how airplanes could shed water more quickly to prevent ice buildup. The longer a water droplet sits on a wing, the greater chance it has of freezing. Intuition would suggest that a smooth surface would more readily cast off water, but James Bird of Boston University, Kripa Varanasi of MIT, and their colleagues were curious if that was really the case.

James Gorman, writing for the New York Times:

They tested ways to shorten the amount of contact time, and recorded the tests with high-speed video, which they analyzed. A smooth surface might seem most likely to repel water, but they found that a rough surface, with ridges, for example, worked better.

The key is that rough textures don’t allow droplets to interact with the surface itself—they keep a layer of air between the material and the liquid. When a droplet hits a surface, it spreads out and then rebounds, sucking back into itself and leaping off the surface—the characteristic “splash.” Rough surfaces quicken that rebound. Many plant leaves use this to their advantage.

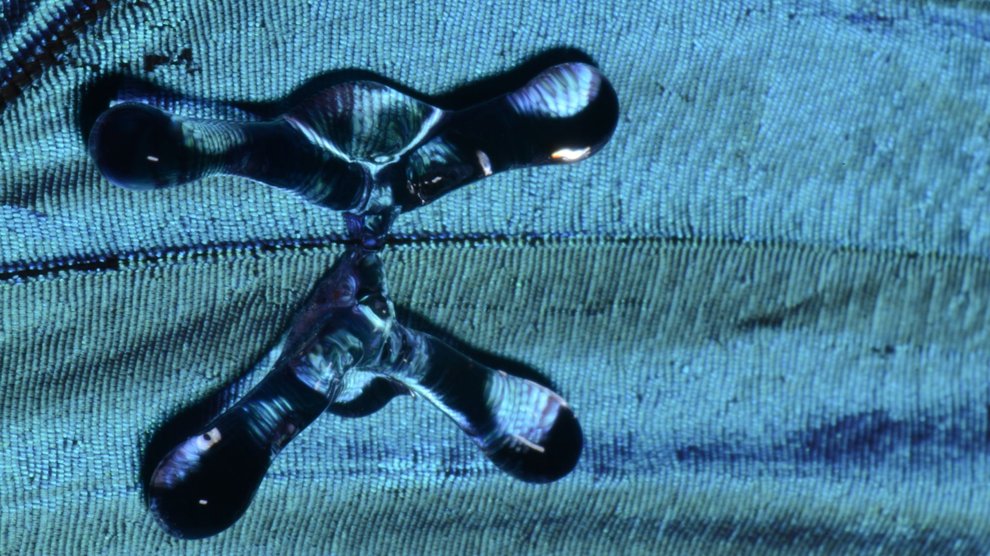

Bird, Varanasi, and their colleagues took the idea one step further. By covering the material with small ridges, they found that water droplets were split in two when they hit. The smaller drops then rebounded 40% faster than on non-ridged surfaces. That reduces the amount of time water sits on the material, reducing the probability that the surface will stay wet. If it’s an airplane wing, there’s a lower chance it will from a dangerous sheen of ice.

The researchers weren’t the first to figure this out. Morpho butterflies and nasturtium plants both have ridges that repel water remarkably well.