Ultracold Experiment Could Solve One of Physics's Biggest Contradictions

There’s a mysterious threshold that’s predicted to exist beyond the limits of what we can see. It’s called the quantum-classical transition.

If scientists were to find it, they’d be able to solve one of the most baffling questions in physics: why is it that a soccer ball or a ballet dancer both obey the Newtonian laws while the subatomic particles they’re made of behave according to quantum rules? Finding the bridge between the two could usher in a new era in physics.

We don’t yet know how the transition from the quantum world to the classical one occurs, but a new experiment, detailed in Physical Review Letters , might give us the opportunity to learn more.

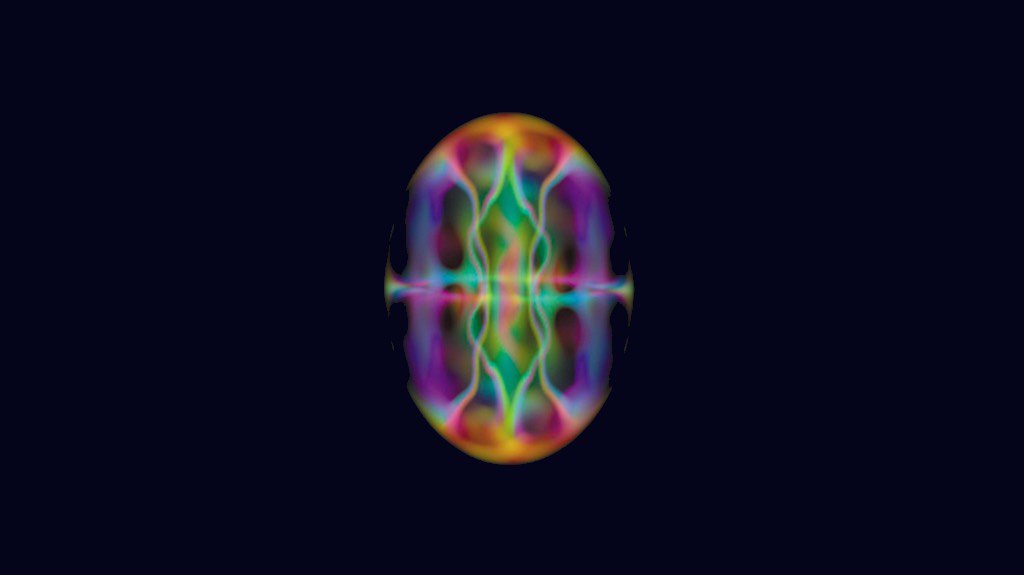

The experiment involves cooling a cloud of rubidium atoms to the point that they become virtually motionless. Theoretically, if a cloud of atoms becomes cold enough, the wave-like (quantum) nature of the individual atoms will start to expand and overlap with one another. It’s sort of like circular ripples in a pond that, as they get bigger, merge to form one large ring. This phenomenon is more commonly known as a Bose-Einstein condensate, a state of matter in which subatomic particles are chilled to near absolute zero (0 Kelvin or −273.15° C) and coalesce into a single quantum object. That quantum object is so big (compared to the individual atoms) that it’s almost macroscopic—in other words, it’s encroaching on the classical world.

The team of physicists cooled their cloud of atoms down to the nano-Kelvin range by trapping them in a magnetic “bowl.” To attempt further cooling, they then shot the cloud of atoms upward in a 10-meter-long pipe and let them free-fall from there, during which time the atom cloud expanded thermally. Then the scientists contained that expansion by sending another laser down onto the atoms, creating an electromagnetic field that kept the cloud from expanding further as it dropped. It created a kind of “cooling” effect, but not in the traditional way you might think—rather, the atoms have a lowered “effective temperature,” which is a measure of how quickly the atom cloud is spreading outward. At this point, then, the atom cloud can be described in terms of two separate temperatures: one in the direction of downward travel, and another in the transverse direction (perpendicular to the direction of travel).

Here’s Chris Lee, writing for ArsTechnica:

This is only the start though. Like all lenses, a magnetic lens has an intrinsic limit to how well it can focus (or, in this case, collimate) the atoms. Ultimately, this limitation is given by the quantum uncertainty in the atom’s momentum and position. If the lensing technique performed at these physical limits, then the cloud’s transverse temperature would end up at a few femtoKelvin (10 -15 ). That would be absolutely incredible.

A really nice side effect is that combinations of lenses can be used like telescopes to compress or expand the cloud while leaving the transverse temperature very cold. It may then be possible to tune how strongly the atoms’ waves overlap and control the speed at which the transition from quantum to classical occurs. This would allow the researchers to explore the transition over a large range of conditions and make their findings more general.

Jason Hogan, assistant professor of physics at Stanford University and one of the study’s authors, told NOVA Next that you can understand this last part by using the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. As a quantum object’s uncertainty in momentum goes down, its uncertainty in position goes up. Hogan and his colleagues are essentially fine-tuning these parameters along two dimensions. If they can find a minimum uncertainty in the momentum (by cooling the particles as much as they can), then they could find the point at which the quantum-to-classical transition occurs. And that would be a spectacular discovery for the field of particle physics.

Image credit: NIST