After Shelby, Voting-Law Changes Come One Town at a Time

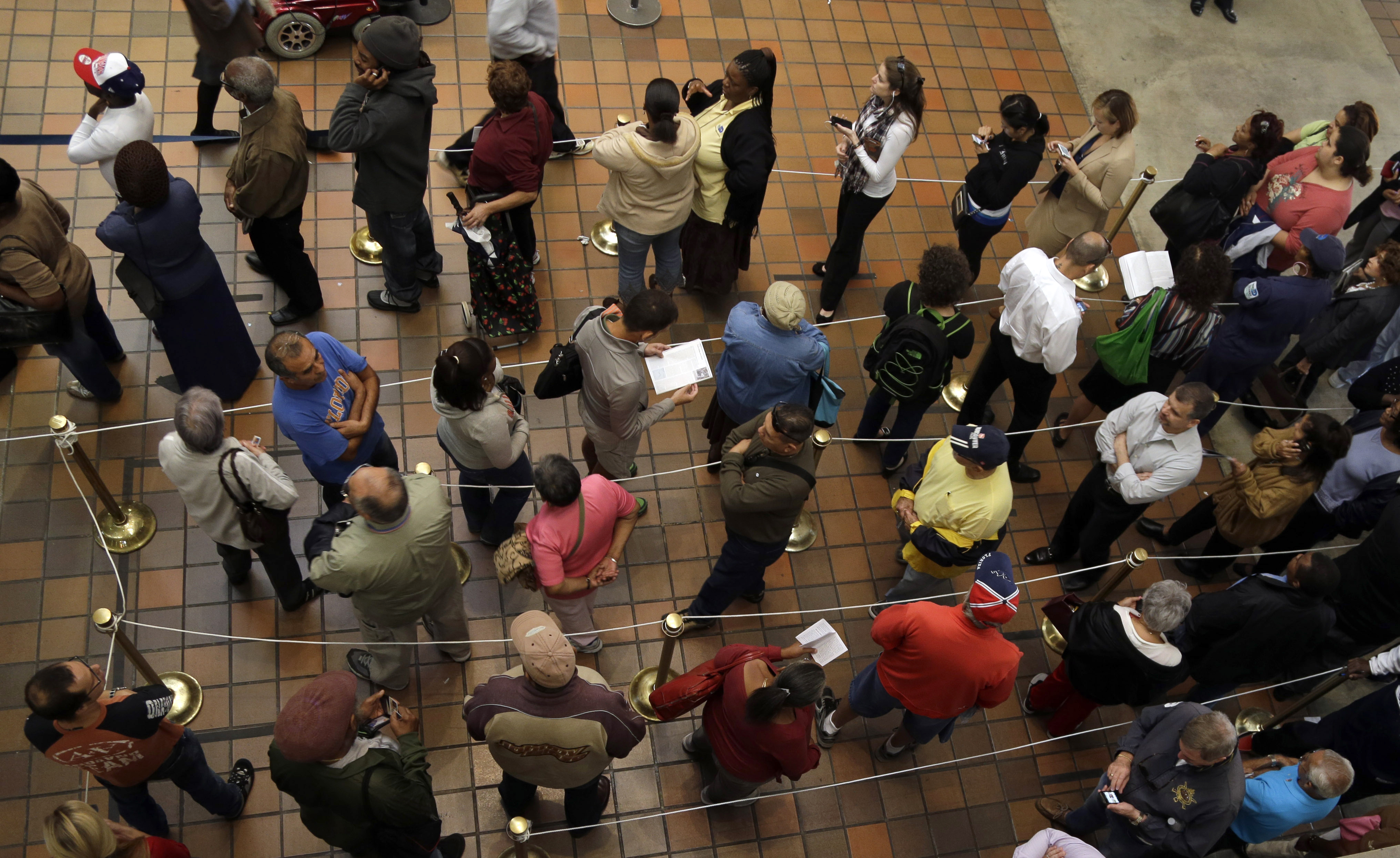

FILE - This Oct. 29, 2012 file photo shows people standing in line to vote during early voting for the presidential election, in Miami. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky, File) (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky, File)

Just over a month after the Supreme Court overturned a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, seven states — five of which were covered under the law — are moving ahead with voting changes that could affect the 2014 Congressional election.

The Justice Department has sued Texas to prevent new voting changes and threatened to step in elsewhere.

But the battle for the ballot box isn’t going to be waged on the national level, or even the state level, voting-rights advocates say. It’s going to be fought in cities and small towns, at the level of county seats, school boards and city councils.

That’s where 85 percent of the DOJ’s Section 5 objections have been under the Voting Rights Act since it was passed. And that’s where legal challenges, the only remaining remedy to fight voter discrimination, are likely to take place, said Dale Ho, head of the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project.

“That’s what we’re really worried about,” Ho said, adding: “I need more lawyers.”

An Early-Warning System in the “Magic City”

In Alabama, a formerly pre-cleared state, a small cadre of attorneys is bracing for a fight.

One of them is Tameka Wren, the president of the Magic City Bar Association in Birmingham. The association, named for an old moniker for the city, is predominately for black lawyers and was formed back when African-Americans weren’t welcome in the main bar association.

A young attorney, who sometimes in her work as a public defender represents the occasional Klansman, Wren sat down and read the Shelby briefs earlier this year.

“I did not realize the breadth of the Voting Rights Act and how it’s used,” she said. “But I know what we sacrificed as minorities, as African-Americans, when we had no hope, no future, no promise, and I don’t want to go back there.”

After the verdict, Wren and another attorney, Raymond Johnson, got together with voting-rights veterans, judges, civil and political leaders, to talk about how to confront challenges to voting laws. They formed the Voting Rights Education Association, which they hope will act as an early-warning system to track proposed voting changes and train lawyers on how to fight them in court.

Wren is putting together a spreadsheet of the voting laws for Alabama’s several hundred local jurisdictions, including requirements for how changes need to be communicated, for example, whether they have to be posted in the town, or online. She is also looking for advocates in those areas willing to report on any changes.

Ultimately, they hope to partner with organizations across the south and in western states, like Texas, to coordinate a legal response. The attorneys say that while they’re grateful for the Justice Department’s recent intervention in Texas, “the DOJ’s going to have their hands full,” Johnson said. “I don’t think they have the manpower.”

The At-Large Voting Problem

Veteran Alabama civil-rights attorney Edward Still said the young lawyers have reason to be concerned.

Still said he has tried dozens of voting-rights cases in his four decades as an attorney. His website is topped with a picture of Birmingham’s classic skyline with the slogan: “We Dare Defend Your Rights.”

“I’ve always got a voting case going on,” he said.

When Still began trying cases, most jurisdictions had moved beyond what he calls “first-generation” voting discrimination cases. He noticed a particular problem with a practice known as “at-large voting,” in which a simple majority of all voters determines the outcome of an election, rather than voters casting ballots by district.

Back before the Voting Rights Act, at-large voting was widely used as a way to promote good governance. The belief was that all council members would be held accountable for what happened in a city, for example, rather than feeling responsible only for their district.

But after the Voting Rights Act was passed, states under preclearance began to use at-large voting as a way to dilute the black vote. At-large voting systems were viewed as the “most significant” cause of diluting the minority vote when the law was first passed, according to Michael Carvin, an attorney at Jones Day law firm in D.C., in his testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee in July.

As the minority group in the majority-rules system, blacks would never be able to elect a candidate of their choice.

“It wasn’t, ‘Hey, these black people should be allowed to vote,’ but rather, ‘You can’t have at-large elections so these black people can’t elect anybody,’” Still said.

Beginning in 1986 for more than a decade, Still litigated a spate of major cases against at-large voting in Alabama, which became known as the Dillard cases.

A U.S. district court found that nearly 200 jurisdictions in the state were using at-large voting to discriminate against blacks. Most of them ultimately agreed to consent decrees requiring them to adapt new voting systems. Some refused and a new system had to be adjudicated by the court.

Now that pre-clearance is gone, Still and other voting-rights advocates, including the ACLU’s Ho, say it’s one of the changes they fear will begin to creep back into favor. With so many tiny jurisdictions, many of them in rural areas, it may be difficult even to know about these changes in time to mount a legal challenge to stop them, they warn.

“We will not tolerate discrimination in Alabama,” said Gov. Robert Bentley, in a statement welcoming the Shelby verdict as as “historic.”

“Alabama has made tremendous progress over the past 50 years, and this decision by the U.S. Supreme Court recognizes that progress.”

Beyond Alabama

At-large voting has been under fire in a number of other states in recent years with California seeing a spate of recent legal challenges. Last month, the Justice Department won a lawsuit against the city of Palmdale, population 158,000, charging that its at-large voting system was discriminatory against Latinos. This week, the city of Whittier, population 86,000, was sued by a coalition of Latino groups, who allege that the city’s at-large voting system prevents Latinos from being elected to the council.

In May, a judge ruled that Fayetteville, Ga., population 16,000, must abandon its at-large voting system, following a lawsuit by the NAACP, which argued it kept blacks from being elected to the city council. The council is appealing the decision.

In Pasadena, Texas, whose 152,000 residents include a burgeoning Latino population, the mayor has proposed changing two district council seats to an at-large vote, city council members say. The proposal would have to be put to a city-wide vote.

Benson, N.C., population 3,382, has three district seats and three that are at-large. Residents can only vote for one at-large seat every three years, the result of a federal court ruling in 1988 that found that the city’s system violated the Voting Rights Act. Now, Benson is considering lifting the limits on at-large voting.

“I’m not sure it’s as needed today as it was when it was put in place,” the mayor, Will Massengill, told the local Smithfield-Herald. “Hopefully, we’re judging people more on what they bring to the table than what their race is.”